Racing Through the 70’s

During the late 60’s and early 70’s whitewater kayaks were hard to find and kayak schools didn’t exist.

You learned to boat from the guys at the local paddling club if you were lucky, or by trial and error if you weren’t. If you were serious about running hard whitewater, you raced. My buddies and I stumbled on racing in the spring of 1969. We’d been paddling open canoes for several years while going to college in Central Pennsylvania. We ran lots of Class II, struggled with some Class III, and wanted to try harder stuff. One weekend we found the Loyalsock Races by accident while running shuttle. Those guys in their sleek 13-foot long slalom kayaks looked pretty hot. We stopped and talked to the racers. My buddies bought a couple of used kayaks there, and I later went home to New York City and bought a new Klepper for $200. Now all we had to do was learn how to paddle them.

The Penn State Outing Club had been a big presence at the Loyalsock Slalom.

Their campus was only an hour from ours, so I wrote them, asking for help in getting started. My letter was answered by someone named John R. Sweet, who invited us to their pool sessions. We arrived to find their group dominated by serious racers. Sweet and Norm Holcombe, both top-ranked C-1 racers, were working with Tom Irwin, an “up and coming” C-1 racer. Steve Draper and Frank Shultz were dancing their end-hole C-2 through the complex “English Gate” sequence. Draper and Jon Nelson, the best kayakers we’d ever seen, nailed hand rolls and flew through gates. We were impressed. We soon learned that the State College area was a major center of whitewater racing nationally. Penn State Outing Club Canoeists had been a force to be reckoned with at national races since the days of Bill Bickham and Dave Guss. The Wildwater Boating Club and Explorer Post 32, both coached by Dave Kurtz in nearby Bellefonte, PA, produced many of hot young paddlers. In addition to Draper and Shultz, their roster included Les Bechdel, Keith Backlund, Steve Martin, Johnny Fisher, and Drew Hunter. We could not have found better teachers.

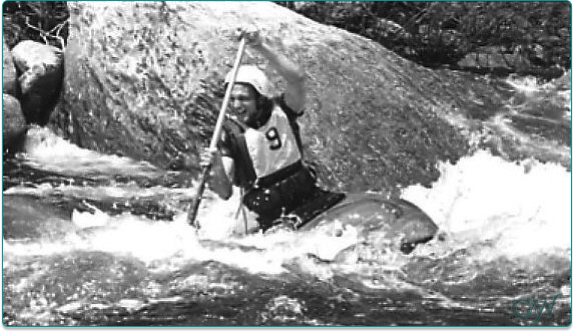

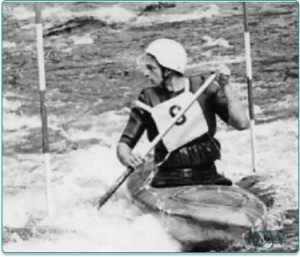

Slalom racing involves maneuvering through gates, which are pairs of poles hanging above the water. The poles are exacting teachers: your boat is either where it’s supposed to be, or it’s not. When you hit a pole in a race, you get a 10-second penalty; miss a gate and you lose 50 seconds. Gates are placed in moving water to take advantage of the current, and it may require a series of lightning-quick linked moves to paddle a tight sequence clean. It takes plenty of skill to run even an easy course without smacking the poles. Sometimes the course was designed to require that you run a big drop backwards. Eddy gates would make you or break you; and getting in and out fast was really hard! Wildwater racing, a straight timed run downriver, was more straightforward and a lot more work. I didn’t get involved with that discipline until later.

Slalom racing involves maneuvering through gates, which are pairs of poles hanging above the water. The poles are exacting teachers: your boat is either where it’s supposed to be, or it’s not. When you hit a pole in a race, you get a 10-second penalty; miss a gate and you lose 50 seconds. Gates are placed in moving water to take advantage of the current, and it may require a series of lightning-quick linked moves to paddle a tight sequence clean. It takes plenty of skill to run even an easy course without smacking the poles. Sometimes the course was designed to require that you run a big drop backwards. Eddy gates would make you or break you; and getting in and out fast was really hard! Wildwater racing, a straight timed run downriver, was more straightforward and a lot more work. I didn’t get involved with that discipline until later.

The next year, after many pool sessions and runs down local rivers, my group entered the Loyalsock Slalom.

Flowing through World’s End State Park in north-central Pennsylvania, it is one of the coldest places around. There were snow flurries on and off during that late April weekend. Despite this, the hotshot Wildwater Boating Club kids, too broke to afford wetsuits, were running around barefoot wearing only shorts and a paddle jacket! The race was a full 30 gates long, culminating in a tight series set in the “sluice”, a break in a 4-foot high low-head dam. We’d run this powerful Class III drop in open canoes the previous spring after much scouting. Now we were in a course that required us to drop over the sluice backwards, go through a gate, spin forward quickly to catch another gate, then charge into an eddy for a third. Because Norm Holcombe said I was too big for a kayak, I had traded in my Klepper for a new John Berry C-1. I wasn’t very good, and I got lots of roll practice in that icy water. My buddies didn’t finish too well, either, but we agreed that racing taught us many things that river running didn’t.

Races were also the best place to check out the latest equipment.

Outdoor stores didn’t carry whitewater gear, and almost everything was home-made. The kayaks and C-boats we used for general river running were the bastard offspring of boats brought back by U.S. team members from Europe. Molds were made from European designs as soon as they arrived in the US. Then, after the mold-maker made a boat for himself, the mold was rented to out to others. Often someone would then take the mold to a distant city, make a boat, and immediately pull a mold from that boat! Molds and materials frequently changed hands at races. Some competitors were engineers with access to unique or exotic materials like Kevlar or carbon fibers, which were likewise passed around. People wandered between the boats lined up on shore near the start, discussing new boat-building and outfitting techniques. You could learn a lot by being there.

A few paddlers made extra money by producing whitewater gear in their spare time and selling it at the races. Some of this stuff was cutting edge. I saw my first neoprene sprayskirt, made by Tom Johnson in California, at a pool slalom in the late 60’s. A year or two later, tired of my flimsy nylon fabric sprayskirt, I bought some neoprene from George Hendricks then found a friend who taught me to make my own. Several years later I’d started a business, selling life vest, wet suit, and sprayskirt kits from the back of my truck at races. My customers provided lots of feedback, and I kept modifying my products until they were right.

A few paddlers made extra money by producing whitewater gear in their spare time and selling it at the races. Some of this stuff was cutting edge. I saw my first neoprene sprayskirt, made by Tom Johnson in California, at a pool slalom in the late 60’s. A year or two later, tired of my flimsy nylon fabric sprayskirt, I bought some neoprene from George Hendricks then found a friend who taught me to make my own. Several years later I’d started a business, selling life vest, wet suit, and sprayskirt kits from the back of my truck at races. My customers provided lots of feedback, and I kept modifying my products until they were right.

Citizen racers comprised the majority of the entries at every race.

They competed five or six times a year and traveled great distances to enter events. Kayakers and C-boaters were so rare back then that two cars travelling in opposite directions carrying whitewater boats would stop so the drivers could get out and talk – even if they were roaring down an interstate! But at a race there were dozens, even hundreds of us! Every few weeks the group converged on a different race site, so you quickly got to know a lot of people. They were a great source of information on local rivers; you could even get an invitation paddle with them on their home waters. We’d coach and cheer each other during the race, then take off later for a quick run down the river. Afterwards, we’d talk gear and rivers around a campfire until late at night. Paddlers of all ages and abilities mixed freely, like a big extended family. Even the most successful racers were generous with their advice. Often I’d arrive at a race site well after midnight, exhausted, only to stay up for several more hours chatting excitedly.

Racing was the focus of serious whitewater paddlers in the seventies, and it changed the sport significantly.

The top racers, who were either going to school or holding down jobs, were known and respected in the same way that rodeo stars are today. Because the sport was so small, even the best paddlers were accessible to everyone. There was no “old school” or “new school”; we were all in the same school, influenced by the rivers, the events, and each other. To be known as a “precision paddler” was a high compliment. (this term survives in the name of Precision Rafting, an Upper Yough outfitter in Friendsville, Maryland) Once I graduated from college I had the time and money to travel the Mid-States race circuit. Each race had a distinct flavor. Here are a few of my favorites:

The Penn State Pool Slalom in February drew competitors from Philadelphia, Baltimore, DC, and Pittsburgh. It was a great way to “jump-start” the racing season, and we all wanted to know who was training seriously. Similar events were put on in most major cities, and some of us attended two or three of them during the winter months. It was not unusual for novice paddlers to compete against seasoned experts just for the experience.

In late March The Petersburg Races, held on the North Fork of South Branch of the Potomac in West Virginia, drew a huge crowd. It consisted of a slalom race, a serious downriver event, and a “cruiser class” on the easier water upstream of Hopeville Canyon. In addition to the hundreds of “locals” from neighboring states, you’d see Southerners from Atlanta, Charlotte and Knoxville and Midwesterners from Chicago, Madison, and Minneapolis. The race eventually got so large that it overwhelmed the resources of this beautiful valley. Campgrounds, restaurants, and other facilities were overloaded, and people parked by the dozens along wide stretches of road and camped out. Finally, in the late seventies, the race coincided with the spring break at several West Virginia colleges. The college kids cut through farmer’s fences and drove their vehicles right down to the river’s edge. Here they amused themselves by throwing beer cans at passing racers, starting fires, tearing up the fields, and generally acting like idiots. Sheep and cows escaped through holes in the fence and wandered out into the road. Several got hit by cars. Traffic was heavy, and there were several serious accidents. It was more than the area’s small police force could manage, and the locals who had sponsored the race for over twenty years decided not to run it the future.

In mid-April I went to races held in the Tarifville Gorge near Hartford, Connecticut. This was an opportunity to compete against the New Englanders, especially the crew from the Ledyard Canoe Club of Dartmouth College. Jay Evans, a Dartmouth admissions officer, was an early leader in the sport. As the advisor to the Ledyard Canoe Club, he coached people like John Burton, Wick Walker, Dave and Peggy Nutt, and Sandy Campbell. His son, Eric, was national kayak champion for over a decade. Eric won many of his races by a few seconds, but as a buddy of mine said, to do that once is lucky, to do it time after time is something else again! Jay was also the U.S. Whitewater Team Coach.

In mid-April I went to races held in the Tarifville Gorge near Hartford, Connecticut. This was an opportunity to compete against the New Englanders, especially the crew from the Ledyard Canoe Club of Dartmouth College. Jay Evans, a Dartmouth admissions officer, was an early leader in the sport. As the advisor to the Ledyard Canoe Club, he coached people like John Burton, Wick Walker, Dave and Peggy Nutt, and Sandy Campbell. His son, Eric, was national kayak champion for over a decade. Eric won many of his races by a few seconds, but as a buddy of mine said, to do that once is lucky, to do it time after time is something else again! Jay was also the U.S. Whitewater Team Coach.

The rivalry between the Ledyard-ites and the top Mid-States paddlers was fierce.

We referred to them (amongst ourselves) as “the green goons” because of their sharp green warm-up outfits. But they were all right, mostly. At spring flows Tarrifville Gorge develops some pretty good sized holes. One year Tom Irwin “accidentally” dropped his paddle during a practice run and hand-surfed the biggest one to everyone’s amazement. An informal ender and hole-riding competition, a precursor of rodeo, began as soon as the race ended. There were pictures of Wick Walker showing off in a 1968 AW Journal, the first copy of the magazine I ever saw.

Races like Tarrifville were put on by the competitors themselves.

When local volunteer sponsors were thin, you would find yourself stringing the gates the morning before the race. Competitors were each assigned jobs like gate judging, timing, and safety. A few non-paddling spouses played key roles, and some, like Rosemary Bridge and Bonnie Bliss, became better known than their famous paddling husbands. At big races boats were checked to see that they met the minimum length and width requirements. If they passed, a design was stenciled on their deck. Then as the season progressed, you could see where people had been by looking at their boats! Many home-made craft wouldn’t pass, but we were all boatbuilders, so it was a simple matter to place a glob of fiberglass mat along the sides or to build up a worn-out bow with scraps of foam and cloth.

I hated gate judging. Things happened so fast, and sometimes you really just couldn’t see what had occurred! Fortunately, we worked in groups, so we could discuss it. I also learned to note exactly what we saw if a top competitor made a touch so we could defend the call if there was trouble later. For example, in addition to writing “10” as the score for a gate, I’d note: “hit the green pole with tip of his stern”. Sometimes friends of a competitor would follow him down as he made his run. They might check your judging sheets and give you a hard time! One year my partner and I had a loud argument with the formidable Canadian Hermann Kerckhoff over a touch that cost his daughter Claudia a top finish. We were saved when the race organizer came by and told Hermann to pony up five bucks and file a protest like everyone else. The disagreement was aired further, in front of the protest committee. I never wanted that job!

When you raced you were at the mercy of the elements.

Tarrifville, for example, often had wicked upstream winds. One racer would have a great run because the poles were blown high off the water by a strong gust, and the next one would get all kinds of penalties when the wind died down and left the poles swinging. You could also end up running just behind a “turkey” who hit lots of poles and set them in motion. As I became more knowledgeable I’d ask the starter to change my race order so a top racer could run ahead of me. If that didn’t work, I’d ask them to increase the interval between our starts. Later, as I got better, I’d do the same thing, but in reverse. Gate judges had whistles so they could signal a paddler who was being overtaken to get off the course. If the boat ahead interfered with your run, you got a re-run, but by the end of a long course the idea of dragging your boat back upstream and going again had little appeal. Luck is always a factor in slalom, and bad luck can ruin months of hard work . Rich Weiss was denied a medal at the World Championships because of a bad gate judging call. The waves, not his boat, set a pole in motion! When I offered my sympathy, he shrugged and said, “that’s slalom.”

The Lower Yough was a popular site for races.

The wildwater races held here in May took advantage of the late spring flows, creating a course that alternated between powerful rapids and fast-moving flat water. Slalom races were usually held at Dartmouth Rapid, so named because the Ledyard paddlers would travel down from New Hampshire during Spring Break and set up a slalom course for training. Then in early September the Keelhauler’s Canoe Club ran a huge slalom that drew several hundred racers. The action started at 8:00 AM and continued until 6:00 PM, with breaks to allow commercial and private paddlers to pass through the course. We’d all scream, “Don’t touch the poles” as they floated through, but sometimes a rafter would grab a slalom pole and pull it down. The race would stop until the damage was repaired. The first time I raced there the course was set in Entrance Rapid. This was an interesting venue, especially when the water rose from 2’ to 4’ in a single day! By my second run things were getting intense. I charged into an upstream gate hung over what had been a mellow hole on river left. As I surfed out to my offside, I realized that it was a LOT bigger than I remembered. I got trashed and ended up swimming all the way down to Cucumber Run. My score for the run was listed as “DNF” for “did not finish”. A paddler who swam was said to have “DNF-ed.”

The wildwater races held here in May took advantage of the late spring flows, creating a course that alternated between powerful rapids and fast-moving flat water. Slalom races were usually held at Dartmouth Rapid, so named because the Ledyard paddlers would travel down from New Hampshire during Spring Break and set up a slalom course for training. Then in early September the Keelhauler’s Canoe Club ran a huge slalom that drew several hundred racers. The action started at 8:00 AM and continued until 6:00 PM, with breaks to allow commercial and private paddlers to pass through the course. We’d all scream, “Don’t touch the poles” as they floated through, but sometimes a rafter would grab a slalom pole and pull it down. The race would stop until the damage was repaired. The first time I raced there the course was set in Entrance Rapid. This was an interesting venue, especially when the water rose from 2’ to 4’ in a single day! By my second run things were getting intense. I charged into an upstream gate hung over what had been a mellow hole on river left. As I surfed out to my offside, I realized that it was a LOT bigger than I remembered. I got trashed and ended up swimming all the way down to Cucumber Run. My score for the run was listed as “DNF” for “did not finish”. A paddler who swam was said to have “DNF-ed.”

My non-racing friends always said that races must be pretty boring because you have to sit around all day to make two three-minute runs. Clearly they weren’t with my group! On the Yough, for example, we’d be on the river at dawn for practice runs. We kept it up until the race officials ran us off. Then many of us would enter two, or even three, classes! After our race runs, we paddled the river. We’d surf ourselves silly at Swimmer’s Rapid and reach the old Stewarton takeout at dusk. Dinner at Glissan’s Restaurant never tasted so good! Since Ohiopyle State Park hadn’t built their campground yet, we then retreated into the countryside to car-camp. Sometimes we’d park in an outfitter’s parking lot, but more secluded locations were preferable. Places like “the gravel pit” (now somebody’s house), “the strip mine”, “the old church” (rude boaters got us thrown out by drinking beer there one Sunday morning), and “the water tower” (my favorite) were gems you shared only with your closest friends. I often woke there on misty mornings, high on the hill above Ohiopyle, to the sound of cars rattling the timbers on the roadbed of the old Yough bridge.

The Icebreaker Slalom was held on a small, dam controlled creek near Unadilla, New York.

This was a popular end-of season event; a chance for Mid-States boaters to race in gates and see their buddies before winter set in. The water was Class II at best, but the gates, especially under the bridge, were tight and challenging. I was living in Philly then, so I joined the Philladelphia Canoe Club. Although we had had only seventy members, more than fifty of them drove four hours up to the race. We had some world class C-2 teams (Chamberlin and Stahl; Dyer and Cass, and Knight and Knight), but the rest of us were also-rans. But because we got one point for each person who finished the course we always outscored mighty Penn State for the team trophy. It was here, in 1974, that a racer attempting to stand up in the middle of the course during a swim caught his foot on the bottom of the river and drowned. We didn’t know what foot entrapment was back then. What impressed me was that about a dozen Yough River guides were on the scene. They were the best river rescuers any of us knew, and could do nothing to help despite the easy whitewater. My write-up of this accident, which coined the term “foot entrapment”, was the beginning of a long career in accident reporting and river safety.

After the race we faced the nasty job of taking down the course. Many of us tried to skip out so we could go paddling! Another hassle was getting the competitors to turn in their numbered bibs. A $5 deposit was taken with your entry, to be given back when the bib was returned. Alternatively, someone to sat at the finish and collected bibs Usually the race chairman and a few loyal friends tidied up the loose ends. I had a lot of respect for all the folks who made my fun possible.

My favorite event was Western Maryland’s Savage River Races.

Joe Monahan, an active C-1 paddler in the sixties and seventies, lived in nearby Cumberland. Although not a top racer himself, he was a great river runner who’s list of first descents included a run down the Upper Blackwater in 1971! He discovered the Savage River, and being a friendly fellow, developed a relationship with him. He was often able to persuade the damkeeper to release an hour or so of water for a case of beer. He was impressed with the five miles of continuous Class III-IV rapids he encountered and told his friends, including some racers from D.C. and Penn State. They made the trip, and decided that the Savage had the potential for a slalom course that would rival the speed and intensity of the great European sites at Merano, Tacen, and Spittal. The Savage Races were born!

Joe Monahan, an active C-1 paddler in the sixties and seventies, lived in nearby Cumberland. Although not a top racer himself, he was a great river runner who’s list of first descents included a run down the Upper Blackwater in 1971! He discovered the Savage River, and being a friendly fellow, developed a relationship with him. He was often able to persuade the damkeeper to release an hour or so of water for a case of beer. He was impressed with the five miles of continuous Class III-IV rapids he encountered and told his friends, including some racers from D.C. and Penn State. They made the trip, and decided that the Savage had the potential for a slalom course that would rival the speed and intensity of the great European sites at Merano, Tacen, and Spittal. The Savage Races were born!

Joe and his buddies formed the Appalachian River Runner’s Federation (the ARRF’s) to run events there. The first few slalom races in the late 60’s were much more intense than anything seen in the U.S. before. Many racers swam, and rescuing their boats was difficult because the rapids were so continuous. The carcasses of their canoes and kayaks were carried down to the Potomac where they ended up in the intakes of the WESVACO Paper Mill in Luke, Maryland. Dave Demaree, who lived along the Savage, used to go to the plant after races to see if anything good had washed up. By my first race in 1971 there were two races a year: one in the Spring, and one in the Fall. Paddling the river after the race at 1000 cfs became one of my favorite things, especially in the area of the “Triple Drops” and “Memorial Rock”. The river had everything – tiny eddies, wicked fast ferries, quick spins in holes, and powerful waves! To play the river you had to be very, very quick. It’s speed and power taught me a great deal about paddling and sharpened my technique. Sometimes during the fall race hot air hit the icy water, creating an almost impenetrable mist. When racing downriver you sometimes weren’t sure quite where you were! The Savage became the site of many outstanding races, including the 1972 Olympic Trials, several Pan Am Cup races, and a number of U.S. slalom and whitewater championships.

The Savage was a great river for team racing, which was just an excuse to run the course a second time. You had to get three paddlers through the “team gate” in fifteen seconds. Top racers paddled very close together; the best teams danced down the river in a precision ballet which was a pleasure to watch. If you weren’t that good, you simply gathered everyone in an eddy before proceeding. At my first Savage race in 1971 I ran team with Ed Gertler, who afterwards invited me join him for a run on the Gauley a few weeks later. At another race Phil Allender got sick, and I was asked to race with the ARRF team of Joe Monahan and Todd Martin. These guys were serious party animals. They carried a wineskin down the course and passed it around before attempting the team gate. Naturally I had to continue the tradition.

In the Spring of 1973 I drove down to the Savage in a pouring rain. I was forced to stop and spend the night in a rest area because the weather got so bad. The next day, just outside Luke, a boulder big as a house rolled into the road. Dozens of racers were stuck behind it. We waited an hour or so for road crews to arrive. They dynamited the boulder and pushed the debris aside so we could continue. When we got to the Savage it was running at 2500 cfs, two and a half times what we expected. The speed and power was truly impressive. Many people who made the long drive took one look, then left! Those of us who stayed modified the course and spent the entire morning trying to paddle it. Everybody rolled a lot, but after the first round of practices when a dozen boats were lost there were very few swims. Tom Irwin won the National C-1 Championships with the best run of the day, but the rest of us were happy to survive. After Saturday’s runs I took a wild run trip down the entire river with Bill Kirby, skirting huge holes above the Triple Drops and sneaking Memorial Rock on the far, far left. Late Sunday afternoon Ed Gertler and I went creeking after the race.

Years later I met my wife at the Savage. But that’s another story.

The 1972 Olympics marked a turning point for U.S competitors.

Until now U.S. Team members were either full-time students or held jobs. But in the winter of ‘71-‘72, Jamie McEwan and a group of other racers postponed their other commitments to train with Tom Johnson in Kernville, California. They camped in vans along the Kern River at a spot they called “Peanut Butter Park”. They worked out every day in moving water gates, and that spring they dominated the racing circuit. Several of them made the Olympic Team. When Jamie won his bronze medal in Augsburg, Germany he inspired Jon Lugbill, Davey Hearn, and a whole new generation of whitewater competitors.

In 1973 I qualified for the U.S. Slalom Team Trials, held on the West River in Vermont.

Here I learned that the selection of the U.S. Team was a political event as much as an athletic one. Jay Evans, the coach of the U.S. Whitewater Team, was a dedicated volunteer who had a lot of influence. For years he picked the team himself! He wanted to concentrate his limited financial and coaching resources (everyone paid most of their own expenses) by selecting a small team that was comprised only of people who he thought could win a medal. Most of them, not surprisingly, came from Dartmouth. Mid-States paddlers believed that only Eric Evans and Jamie McEwan had any chance to win a medal. They felt that we should field as large a team as international regulations allowed to allow our athletes to be seasoned by high-level competition. Even those who did not win medals would be valuable to our racing program as coaches and officials. This philosophical difference caused endless argument.

Jay was also not happy about being responsible for teen-aged competitors. He tried to keep Lynn Ashton, Cindy Goodwin, and Louise Holcombe off the Olympic Team because “those teenaged girls” would distract his male kayakers from their training. But they were great competitors, and he was overruled. But this year Kevin Lewis, now an AW director, qualified for the U.S. team in C-1 at age 15. Jay refused to take him because he “was a coach, not a baby-sitter”. There was also a controversy about Steve Draper and Mikki Piras in C-2 Mixed (C-2M). Steve met Mikki, a Penn State varsity gymnast, and convinced her to paddle doubles with him. After training together for less than six months they made the team, beating several more experienced pairs. There was much unhappiness about allowing such a “green” doubles pair to qualify for the team, but they did well in Europe. I was not a contender, so I hung out with friends as the arguments continued until late at night.

Mixed doubles was very challenging mentally.

A man is always going to be physically stronger than his female partner, so it takes excellent communication and plenty of practice to keep a canoe under control in slalom gates. Take two competitive individuals, place them in C-2’s, add whitewater, cook under pressure, and fights will erupt. Add a little sexual tension, and things get pretty hot. I was sitting on shore watching practice runs at Loyalsock when the top four C-2M teams started screaming at each other. It really didn’t matter if they were married, travelling as boyfriend and girlfriend, or simply two athletes training together.

I also remember the impressive team of Chuck Lyda and Marietta Gilman from California. Chuck. At 6’ tall and 180 pounds, he was one of the most powerful whitewater athletes of his era. Mary was a petite blonde, weighing less than 100 pounds, who wore butterfly decals on her helmet. In those days, men paddled bow for maximum power and women controlled the boat from the stern. Marietta maintained control of their boat despite their huge physical differences. The other women who paddled C-2M joked that Chuck was simply paddling a big, heavy C-1. But when they got in the boat with him they could not control it! Unfortunately, C-2M is no longer contested internationally. The Eastern Europeans got tired of having their teams defect, and lobbied hard to eliminate it. But before this happened, the Chladeks and the Sedlviks made their escape from Czechoslovakia. Both couples came to the U.S. and contributed a lot to the sport.

A few weeks later Norm Holcombe and I tried out for the U.S. Wildwater Team in C-2. We lived several hours apart, but planned to work out individually on weekdays and paddle together at the races. We never had a chance. This year several excellent doubles teams trained together daily, including two pairs from Philadelphia and the Braman’s, a father/son team from upstate New York who were active in marathon racing. We finished 6th. But Norm had won a spot the slalom team in C-2M the previous week with his wife, Barb.

In 1974 I worked at the Nantahala Outdoor Center with a number of other racers.

At the end of each day we trained on a slalom course hung from the Appalachian Trail Bridge. There were just four gates, not the elaborate setup you see today. I got into excellent shape. I decided to make a full-scale try for the 1975 U.S. Whitewater Team. But I needed to make a difficult choice. Although I loved slalom, I knew that my chances of making the team in C-1 were very poor. Behind Jamie McEwan were people like Angus Morrison, Tom Irwin, and several other boaters who usually beat me badly. But the competition was much less intense in C-1 wildwater. I made myself a wildwater C-1 and started working out in earnest.

At the end of each day we trained on a slalom course hung from the Appalachian Trail Bridge. There were just four gates, not the elaborate setup you see today. I got into excellent shape. I decided to make a full-scale try for the 1975 U.S. Whitewater Team. But I needed to make a difficult choice. Although I loved slalom, I knew that my chances of making the team in C-1 were very poor. Behind Jamie McEwan were people like Angus Morrison, Tom Irwin, and several other boaters who usually beat me badly. But the competition was much less intense in C-1 wildwater. I made myself a wildwater C-1 and started working out in earnest.

Mikki Piras, who had also worked at NOC, had moved to DC to train for the wildwater team. Through her I met a coach from the U.S. flatwater team, refined my stroke, and developed a training schedule. Back in Philadelphia, training alone, I paddled intense 3-hour daily workouts on the Schulkill River throughout the winter. I only missed a few days due to extreme cold. I took regular whitewater training runs on weekends with the doubles teams from the Philadelphia Canoe Club, covering ten to twenty miles at a fast clip. But solo training was not without its pitfalls! One frigid night my trusty Norse paddle snapped miles downstream, and I found myself swimming in the icy water. Fortunately I was wearing my shorty wetsuit! I quickly swam to shore, stashed my boat, and staggered out to East River Drive. I soon realized that with my large size and strange clothes no one was going to give me a lift. So I ran four miles back to the Philly Canoe Club where I sat in their shower for a long time.

By Spring I was in the best shape of my life. I won a couple of downriver races and even moved up a few positions in slalom. I knew I couldn’t beat Al Button, the muscular ex-marathon racer from Minneapolis who had designed his own wildwater C-1 (the Seagull) and paddled on both sides with equal skill. I thought that Tom Irwin, who I could never compete with, would probably take the second wildwater team slot. But the third spot would be mine!

By Spring I was in the best shape of my life. I won a couple of downriver races and even moved up a few positions in slalom. I knew I couldn’t beat Al Button, the muscular ex-marathon racer from Minneapolis who had designed his own wildwater C-1 (the Seagull) and paddled on both sides with equal skill. I thought that Tom Irwin, who I could never compete with, would probably take the second wildwater team slot. But the third spot would be mine!

That was not to be. A few weeks before the team trials were held on the Yough my workouts started feeling sluggish. I just didn’t have any snap! At the Yough, I took a long warm-up but still didn’t feel right. I did O.K. in the rapids of the loop, but lost lots of time in the long flat stretch between the bottom of Railroad Rapid and the top of Swimmers. In the end, I lost “my” slot to people I had beaten earlier in the season. Looking back on it, I think that I was probably over-trained and should have cut way back on my workouts before the race. But working alone, without a coach, I just didn’t see it. The guys who beat me simply trained smarter. The next day I went over to the Cheat, hopped in my slalom boat, and played the river with total abandon. At the takeout, I wasn’t the least bit tired.

Although I continued to race for several more years, I never trained with that intensity again. As I passed my 30th birthday the children of my citizen racing buddies were reaching maturity. The Lugbill Brothers, Jon and Ron, made the U.S. Team in ’75 at age 14 and 15. They were a great pair, and this time no one griped about their age. In the years that followed they, along with Dave and Cathy Hearn, lead the “D.C. Kids” to worldwide fame. They dominated the 1979 World Championships in Jonquiere, Quebec, Canada. And that was just the beginning.

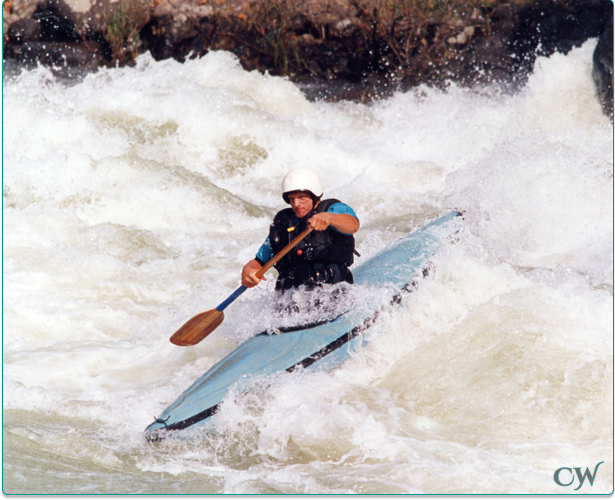

Lugbill and Hearn’s slalom C-1 design, the Max II, revolutionized slalom.

Our old practice of leaning back to “duck” your stern under a pole was much easier in this low-volume design. The “kids” evolved the technique further. Kent Ford told me about one night when the group was practicing at the David Taylor Model Basin, a huge indoor pool used for testing naval ship hulls. They stared competing to see who could sneak under a gate the furthest by lowering one pole down into the water. Soon they decided that it was easier to see whose bow could climb up higher on the opposite pole. This quickly evolved into the stern pivot turn, which lifted the bow out of the water for lighting fast spins. Kayakers watched the C-boaters, learned from them, then re-worked their gear and skills. Racers throughout the world copied them. Later, pioneering West Virginia squirt boaters turned this move into the stern squirt. Many other squirt and rodeo moves evolved from here.

Their coach, Bill Endicott, turned training for whitewater events into a science. The U.S. Slalom Team became the one to beat in international competition. With success came financial support. Where once the athletes camped out at the Worlds and lived on peanut butter, now their expenses were met by sponsors. Eventually elite boaters in each class were “sponsored”. It was exciting to watch this develop. But I couldn’t fit into the small slalom boats or, more importantly, compete with all this young talent. By the late 70’s my finish at big races dropped from “the top ten” to the high teens and beyond. It was time to move on.

I was not alone. When I started paddling, the boat designs that the top competitors used were the same ones that everyone wanted for river running. But this changed when the low-volume boats arrived. Race courses kept getting tighter and tighter until you couldn’t possibly make the moves without one. But these small boats were just too small and unstable for most river runners. As the athletes became more talented, fit and focused it was harder for a citizen racer to realistically aspire to racing glory without also planning to quit their job and train full-time. By the early 80’s the first roto-molded kayaks appeared. The River Chaser was followed by the Mirage, then the Dancer. The Dancer was much too short to be race-legal, but by now no one cared. So ironically, as the U.S. produced more world-class racers than anyone, lots of citizen racers like me dropped out. Attendance flagged, and races that used to draw several hundred competitors ended up with a few dozen. So despite the growth of whitewater kayaking, there are probably fewer racers today than there were in the late 70’s. Racers used to be role models for the whitewater community; now that role is filled by competitors in the booming sport of whitewater rodeo.

By now I realized that I was having more fun running rivers than racing.

I stopped traveling to races, and began working as a safety boater for raft trips on the Cheat River.. By this time you could actually walk into a store and buy a kayak, and paddlers could learn the skills they needed without racing, Most of the strong boaters I ran with in the 80’s, like Johnny Brown, Peter Zurfleigh, Jim Hammil, Al Louande, and Pete Skinner; had no racing in their backgrounds. I began cruising up to northern New York to paddle with Skinner and his bunch. I got called occasionally to help with race safety at the Savage, which was always a good excuse to run the river see old friends. Sadly, releases on this river have been curtailed during the last decade by fishing interests. This is a real loss to paddlers everywhere, and I hope we’ll find ways to get back on the river in the future.

I stopped traveling to races, and began working as a safety boater for raft trips on the Cheat River.. By this time you could actually walk into a store and buy a kayak, and paddlers could learn the skills they needed without racing, Most of the strong boaters I ran with in the 80’s, like Johnny Brown, Peter Zurfleigh, Jim Hammil, Al Louande, and Pete Skinner; had no racing in their backgrounds. I began cruising up to northern New York to paddle with Skinner and his bunch. I got called occasionally to help with race safety at the Savage, which was always a good excuse to run the river see old friends. Sadly, releases on this river have been curtailed during the last decade by fishing interests. This is a real loss to paddlers everywhere, and I hope we’ll find ways to get back on the river in the future.

The International Canoe Federation accepted a U.S. bid to run the World Championships on the Savage In 1989.

For many of us who raced in the 70’s, it was the fulfillment of a long-time dream. Finally, the Euros who we had learned so much from and looked up to for so long were coming here. They, not our guys, would deal with jet lag, bad food, culture shock, and unfamiliar whitewater. I joined many other ex-racers in a three-year effort to make the event work, coordinating a fifty-person safety team. I saw Jon Lugbill make what was arguably the two finest C-1 runs ever seen at a World Championship to win the gold medal. But more than that, I saw a lot of familiar faces along the shore. The old gang was gathering at the river one more time!