Chatting with Charlie

Start at the beginning with Charlie Walbridge in this NRS Duct Tape Diaries.

Find out how Charlie got his start in whitewater along with some of the ups and downs.

Find out how Charlie got his start in whitewater along with some of the ups and downs.

This is a fantastic interview with Charlie Walbridge by Chris Preperato, which shares insight into Charlie’s introduction to the sport of whitewater boating. You can learn more about Charlie, like how Charlie’s Choice Rapid was named by visiting the History of the Upper Yough.

You learned to boat from the guys at the local paddling club if you were lucky, or by trial and error if you weren’t. If you were serious about running hard whitewater, you raced. My buddies and I stumbled on racing in the spring of 1969. We’d been paddling open canoes for several years while going to college in Central Pennsylvania. We ran lots of Class II, struggled with some Class III, and wanted to try harder stuff. One weekend we found the Loyalsock Races by accident while running shuttle. Those guys in their sleek 13-foot long slalom kayaks looked pretty hot. We stopped and talked to the racers. My buddies bought a couple of used kayaks there, and I later went home to New York City and bought a new Klepper for $200. Now all we had to do was learn how to paddle them.

Their campus was only an hour from ours, so I wrote them, asking for help in getting started. My letter was answered by someone named John R. Sweet, who invited us to their pool sessions. We arrived to find their group dominated by serious racers. Sweet and Norm Holcombe, both top-ranked C-1 racers, were working with Tom Irwin, an “up and coming” C-1 racer. Steve Draper and Frank Shultz were dancing their end-hole C-2 through the complex “English Gate” sequence. Draper and Jon Nelson, the best kayakers we’d ever seen, nailed hand rolls and flew through gates. We were impressed. We soon learned that the State College area was a major center of whitewater racing nationally. Penn State Outing Club Canoeists had been a force to be reckoned with at national races since the days of Bill Bickham and Dave Guss. The Wildwater Boating Club and Explorer Post 32, both coached by Dave Kurtz in nearby Bellefonte, PA, produced many of hot young paddlers. In addition to Draper and Shultz, their roster included Les Bechdel, Keith Backlund, Steve Martin, Johnny Fisher, and Drew Hunter. We could not have found better teachers.

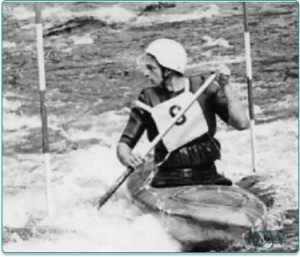

Slalom racing involves maneuvering through gates, which are pairs of poles hanging above the water. The poles are exacting teachers: your boat is either where it’s supposed to be, or it’s not. When you hit a pole in a race, you get a 10-second penalty; miss a gate and you lose 50 seconds. Gates are placed in moving water to take advantage of the current, and it may require a series of lightning-quick linked moves to paddle a tight sequence clean. It takes plenty of skill to run even an easy course without smacking the poles. Sometimes the course was designed to require that you run a big drop backwards. Eddy gates would make you or break you; and getting in and out fast was really hard! Wildwater racing, a straight timed run downriver, was more straightforward and a lot more work. I didn’t get involved with that discipline until later.

Slalom racing involves maneuvering through gates, which are pairs of poles hanging above the water. The poles are exacting teachers: your boat is either where it’s supposed to be, or it’s not. When you hit a pole in a race, you get a 10-second penalty; miss a gate and you lose 50 seconds. Gates are placed in moving water to take advantage of the current, and it may require a series of lightning-quick linked moves to paddle a tight sequence clean. It takes plenty of skill to run even an easy course without smacking the poles. Sometimes the course was designed to require that you run a big drop backwards. Eddy gates would make you or break you; and getting in and out fast was really hard! Wildwater racing, a straight timed run downriver, was more straightforward and a lot more work. I didn’t get involved with that discipline until later.

Flowing through World’s End State Park in north-central Pennsylvania, it is one of the coldest places around. There were snow flurries on and off during that late April weekend. Despite this, the hotshot Wildwater Boating Club kids, too broke to afford wetsuits, were running around barefoot wearing only shorts and a paddle jacket! The race was a full 30 gates long, culminating in a tight series set in the “sluice”, a break in a 4-foot high low-head dam. We’d run this powerful Class III drop in open canoes the previous spring after much scouting. Now we were in a course that required us to drop over the sluice backwards, go through a gate, spin forward quickly to catch another gate, then charge into an eddy for a third. Because Norm Holcombe said I was too big for a kayak, I had traded in my Klepper for a new John Berry C-1. I wasn’t very good, and I got lots of roll practice in that icy water. My buddies didn’t finish too well, either, but we agreed that racing taught us many things that river running didn’t.

Outdoor stores didn’t carry whitewater gear, and almost everything was home-made. The kayaks and C-boats we used for general river running were the bastard offspring of boats brought back by U.S. team members from Europe. Molds were made from European designs as soon as they arrived in the US. Then, after the mold-maker made a boat for himself, the mold was rented to out to others. Often someone would then take the mold to a distant city, make a boat, and immediately pull a mold from that boat! Molds and materials frequently changed hands at races. Some competitors were engineers with access to unique or exotic materials like Kevlar or carbon fibers, which were likewise passed around. People wandered between the boats lined up on shore near the start, discussing new boat-building and outfitting techniques. You could learn a lot by being there.

A few paddlers made extra money by producing whitewater gear in their spare time and selling it at the races. Some of this stuff was cutting edge. I saw my first neoprene sprayskirt, made by Tom Johnson in California, at a pool slalom in the late 60’s. A year or two later, tired of my flimsy nylon fabric sprayskirt, I bought some neoprene from George Hendricks then found a friend who taught me to make my own. Several years later I’d started a business, selling life vest, wet suit, and sprayskirt kits from the back of my truck at races. My customers provided lots of feedback, and I kept modifying my products until they were right.

A few paddlers made extra money by producing whitewater gear in their spare time and selling it at the races. Some of this stuff was cutting edge. I saw my first neoprene sprayskirt, made by Tom Johnson in California, at a pool slalom in the late 60’s. A year or two later, tired of my flimsy nylon fabric sprayskirt, I bought some neoprene from George Hendricks then found a friend who taught me to make my own. Several years later I’d started a business, selling life vest, wet suit, and sprayskirt kits from the back of my truck at races. My customers provided lots of feedback, and I kept modifying my products until they were right.

They competed five or six times a year and traveled great distances to enter events. Kayakers and C-boaters were so rare back then that two cars travelling in opposite directions carrying whitewater boats would stop so the drivers could get out and talk – even if they were roaring down an interstate! But at a race there were dozens, even hundreds of us! Every few weeks the group converged on a different race site, so you quickly got to know a lot of people. They were a great source of information on local rivers; you could even get an invitation paddle with them on their home waters. We’d coach and cheer each other during the race, then take off later for a quick run down the river. Afterwards, we’d talk gear and rivers around a campfire until late at night. Paddlers of all ages and abilities mixed freely, like a big extended family. Even the most successful racers were generous with their advice. Often I’d arrive at a race site well after midnight, exhausted, only to stay up for several more hours chatting excitedly.

The top racers, who were either going to school or holding down jobs, were known and respected in the same way that rodeo stars are today. Because the sport was so small, even the best paddlers were accessible to everyone. There was no “old school” or “new school”; we were all in the same school, influenced by the rivers, the events, and each other. To be known as a “precision paddler” was a high compliment. (this term survives in the name of Precision Rafting, an Upper Yough outfitter in Friendsville, Maryland) Once I graduated from college I had the time and money to travel the Mid-States race circuit. Each race had a distinct flavor. Here are a few of my favorites:

The Penn State Pool Slalom in February drew competitors from Philadelphia, Baltimore, DC, and Pittsburgh. It was a great way to “jump-start” the racing season, and we all wanted to know who was training seriously. Similar events were put on in most major cities, and some of us attended two or three of them during the winter months. It was not unusual for novice paddlers to compete against seasoned experts just for the experience.

In late March The Petersburg Races, held on the North Fork of South Branch of the Potomac in West Virginia, drew a huge crowd. It consisted of a slalom race, a serious downriver event, and a “cruiser class” on the easier water upstream of Hopeville Canyon. In addition to the hundreds of “locals” from neighboring states, you’d see Southerners from Atlanta, Charlotte and Knoxville and Midwesterners from Chicago, Madison, and Minneapolis. The race eventually got so large that it overwhelmed the resources of this beautiful valley. Campgrounds, restaurants, and other facilities were overloaded, and people parked by the dozens along wide stretches of road and camped out. Finally, in the late seventies, the race coincided with the spring break at several West Virginia colleges. The college kids cut through farmer’s fences and drove their vehicles right down to the river’s edge. Here they amused themselves by throwing beer cans at passing racers, starting fires, tearing up the fields, and generally acting like idiots. Sheep and cows escaped through holes in the fence and wandered out into the road. Several got hit by cars. Traffic was heavy, and there were several serious accidents. It was more than the area’s small police force could manage, and the locals who had sponsored the race for over twenty years decided not to run it the future.

In mid-April I went to races held in the Tarifville Gorge near Hartford, Connecticut. This was an opportunity to compete against the New Englanders, especially the crew from the Ledyard Canoe Club of Dartmouth College. Jay Evans, a Dartmouth admissions officer, was an early leader in the sport. As the advisor to the Ledyard Canoe Club, he coached people like John Burton, Wick Walker, Dave and Peggy Nutt, and Sandy Campbell. His son, Eric, was national kayak champion for over a decade. Eric won many of his races by a few seconds, but as a buddy of mine said, to do that once is lucky, to do it time after time is something else again! Jay was also the U.S. Whitewater Team Coach.

In mid-April I went to races held in the Tarifville Gorge near Hartford, Connecticut. This was an opportunity to compete against the New Englanders, especially the crew from the Ledyard Canoe Club of Dartmouth College. Jay Evans, a Dartmouth admissions officer, was an early leader in the sport. As the advisor to the Ledyard Canoe Club, he coached people like John Burton, Wick Walker, Dave and Peggy Nutt, and Sandy Campbell. His son, Eric, was national kayak champion for over a decade. Eric won many of his races by a few seconds, but as a buddy of mine said, to do that once is lucky, to do it time after time is something else again! Jay was also the U.S. Whitewater Team Coach.

We referred to them (amongst ourselves) as “the green goons” because of their sharp green warm-up outfits. But they were all right, mostly. At spring flows Tarrifville Gorge develops some pretty good sized holes. One year Tom Irwin “accidentally” dropped his paddle during a practice run and hand-surfed the biggest one to everyone’s amazement. An informal ender and hole-riding competition, a precursor of rodeo, began as soon as the race ended. There were pictures of Wick Walker showing off in a 1968 AW Journal, the first copy of the magazine I ever saw.

When local volunteer sponsors were thin, you would find yourself stringing the gates the morning before the race. Competitors were each assigned jobs like gate judging, timing, and safety. A few non-paddling spouses played key roles, and some, like Rosemary Bridge and Bonnie Bliss, became better known than their famous paddling husbands. At big races boats were checked to see that they met the minimum length and width requirements. If they passed, a design was stenciled on their deck. Then as the season progressed, you could see where people had been by looking at their boats! Many home-made craft wouldn’t pass, but we were all boatbuilders, so it was a simple matter to place a glob of fiberglass mat along the sides or to build up a worn-out bow with scraps of foam and cloth.

I hated gate judging. Things happened so fast, and sometimes you really just couldn’t see what had occurred! Fortunately, we worked in groups, so we could discuss it. I also learned to note exactly what we saw if a top competitor made a touch so we could defend the call if there was trouble later. For example, in addition to writing “10” as the score for a gate, I’d note: “hit the green pole with tip of his stern”. Sometimes friends of a competitor would follow him down as he made his run. They might check your judging sheets and give you a hard time! One year my partner and I had a loud argument with the formidable Canadian Hermann Kerckhoff over a touch that cost his daughter Claudia a top finish. We were saved when the race organizer came by and told Hermann to pony up five bucks and file a protest like everyone else. The disagreement was aired further, in front of the protest committee. I never wanted that job!

Tarrifville, for example, often had wicked upstream winds. One racer would have a great run because the poles were blown high off the water by a strong gust, and the next one would get all kinds of penalties when the wind died down and left the poles swinging. You could also end up running just behind a “turkey” who hit lots of poles and set them in motion. As I became more knowledgeable I’d ask the starter to change my race order so a top racer could run ahead of me. If that didn’t work, I’d ask them to increase the interval between our starts. Later, as I got better, I’d do the same thing, but in reverse. Gate judges had whistles so they could signal a paddler who was being overtaken to get off the course. If the boat ahead interfered with your run, you got a re-run, but by the end of a long course the idea of dragging your boat back upstream and going again had little appeal. Luck is always a factor in slalom, and bad luck can ruin months of hard work . Rich Weiss was denied a medal at the World Championships because of a bad gate judging call. The waves, not his boat, set a pole in motion! When I offered my sympathy, he shrugged and said, “that’s slalom.”

The wildwater races held here in May took advantage of the late spring flows, creating a course that alternated between powerful rapids and fast-moving flat water. Slalom races were usually held at Dartmouth Rapid, so named because the Ledyard paddlers would travel down from New Hampshire during Spring Break and set up a slalom course for training. Then in early September the Keelhauler’s Canoe Club ran a huge slalom that drew several hundred racers. The action started at 8:00 AM and continued until 6:00 PM, with breaks to allow commercial and private paddlers to pass through the course. We’d all scream, “Don’t touch the poles” as they floated through, but sometimes a rafter would grab a slalom pole and pull it down. The race would stop until the damage was repaired. The first time I raced there the course was set in Entrance Rapid. This was an interesting venue, especially when the water rose from 2’ to 4’ in a single day! By my second run things were getting intense. I charged into an upstream gate hung over what had been a mellow hole on river left. As I surfed out to my offside, I realized that it was a LOT bigger than I remembered. I got trashed and ended up swimming all the way down to Cucumber Run. My score for the run was listed as “DNF” for “did not finish”. A paddler who swam was said to have “DNF-ed.”

The wildwater races held here in May took advantage of the late spring flows, creating a course that alternated between powerful rapids and fast-moving flat water. Slalom races were usually held at Dartmouth Rapid, so named because the Ledyard paddlers would travel down from New Hampshire during Spring Break and set up a slalom course for training. Then in early September the Keelhauler’s Canoe Club ran a huge slalom that drew several hundred racers. The action started at 8:00 AM and continued until 6:00 PM, with breaks to allow commercial and private paddlers to pass through the course. We’d all scream, “Don’t touch the poles” as they floated through, but sometimes a rafter would grab a slalom pole and pull it down. The race would stop until the damage was repaired. The first time I raced there the course was set in Entrance Rapid. This was an interesting venue, especially when the water rose from 2’ to 4’ in a single day! By my second run things were getting intense. I charged into an upstream gate hung over what had been a mellow hole on river left. As I surfed out to my offside, I realized that it was a LOT bigger than I remembered. I got trashed and ended up swimming all the way down to Cucumber Run. My score for the run was listed as “DNF” for “did not finish”. A paddler who swam was said to have “DNF-ed.”

My non-racing friends always said that races must be pretty boring because you have to sit around all day to make two three-minute runs. Clearly they weren’t with my group! On the Yough, for example, we’d be on the river at dawn for practice runs. We kept it up until the race officials ran us off. Then many of us would enter two, or even three, classes! After our race runs, we paddled the river. We’d surf ourselves silly at Swimmer’s Rapid and reach the old Stewarton takeout at dusk. Dinner at Glissan’s Restaurant never tasted so good! Since Ohiopyle State Park hadn’t built their campground yet, we then retreated into the countryside to car-camp. Sometimes we’d park in an outfitter’s parking lot, but more secluded locations were preferable. Places like “the gravel pit” (now somebody’s house), “the strip mine”, “the old church” (rude boaters got us thrown out by drinking beer there one Sunday morning), and “the water tower” (my favorite) were gems you shared only with your closest friends. I often woke there on misty mornings, high on the hill above Ohiopyle, to the sound of cars rattling the timbers on the roadbed of the old Yough bridge.

This was a popular end-of season event; a chance for Mid-States boaters to race in gates and see their buddies before winter set in. The water was Class II at best, but the gates, especially under the bridge, were tight and challenging. I was living in Philly then, so I joined the Philladelphia Canoe Club. Although we had had only seventy members, more than fifty of them drove four hours up to the race. We had some world class C-2 teams (Chamberlin and Stahl; Dyer and Cass, and Knight and Knight), but the rest of us were also-rans. But because we got one point for each person who finished the course we always outscored mighty Penn State for the team trophy. It was here, in 1974, that a racer attempting to stand up in the middle of the course during a swim caught his foot on the bottom of the river and drowned. We didn’t know what foot entrapment was back then. What impressed me was that about a dozen Yough River guides were on the scene. They were the best river rescuers any of us knew, and could do nothing to help despite the easy whitewater. My write-up of this accident, which coined the term “foot entrapment”, was the beginning of a long career in accident reporting and river safety.

After the race we faced the nasty job of taking down the course. Many of us tried to skip out so we could go paddling! Another hassle was getting the competitors to turn in their numbered bibs. A $5 deposit was taken with your entry, to be given back when the bib was returned. Alternatively, someone to sat at the finish and collected bibs Usually the race chairman and a few loyal friends tidied up the loose ends. I had a lot of respect for all the folks who made my fun possible.

Joe Monahan, an active C-1 paddler in the sixties and seventies, lived in nearby Cumberland. Although not a top racer himself, he was a great river runner who’s list of first descents included a run down the Upper Blackwater in 1971! He discovered the Savage River, and being a friendly fellow, developed a relationship with him. He was often able to persuade the damkeeper to release an hour or so of water for a case of beer. He was impressed with the five miles of continuous Class III-IV rapids he encountered and told his friends, including some racers from D.C. and Penn State. They made the trip, and decided that the Savage had the potential for a slalom course that would rival the speed and intensity of the great European sites at Merano, Tacen, and Spittal. The Savage Races were born!

Joe Monahan, an active C-1 paddler in the sixties and seventies, lived in nearby Cumberland. Although not a top racer himself, he was a great river runner who’s list of first descents included a run down the Upper Blackwater in 1971! He discovered the Savage River, and being a friendly fellow, developed a relationship with him. He was often able to persuade the damkeeper to release an hour or so of water for a case of beer. He was impressed with the five miles of continuous Class III-IV rapids he encountered and told his friends, including some racers from D.C. and Penn State. They made the trip, and decided that the Savage had the potential for a slalom course that would rival the speed and intensity of the great European sites at Merano, Tacen, and Spittal. The Savage Races were born!

Joe and his buddies formed the Appalachian River Runner’s Federation (the ARRF’s) to run events there. The first few slalom races in the late 60’s were much more intense than anything seen in the U.S. before. Many racers swam, and rescuing their boats was difficult because the rapids were so continuous. The carcasses of their canoes and kayaks were carried down to the Potomac where they ended up in the intakes of the WESVACO Paper Mill in Luke, Maryland. Dave Demaree, who lived along the Savage, used to go to the plant after races to see if anything good had washed up. By my first race in 1971 there were two races a year: one in the Spring, and one in the Fall. Paddling the river after the race at 1000 cfs became one of my favorite things, especially in the area of the “Triple Drops” and “Memorial Rock”. The river had everything – tiny eddies, wicked fast ferries, quick spins in holes, and powerful waves! To play the river you had to be very, very quick. It’s speed and power taught me a great deal about paddling and sharpened my technique. Sometimes during the fall race hot air hit the icy water, creating an almost impenetrable mist. When racing downriver you sometimes weren’t sure quite where you were! The Savage became the site of many outstanding races, including the 1972 Olympic Trials, several Pan Am Cup races, and a number of U.S. slalom and whitewater championships.

The Savage was a great river for team racing, which was just an excuse to run the course a second time. You had to get three paddlers through the “team gate” in fifteen seconds. Top racers paddled very close together; the best teams danced down the river in a precision ballet which was a pleasure to watch. If you weren’t that good, you simply gathered everyone in an eddy before proceeding. At my first Savage race in 1971 I ran team with Ed Gertler, who afterwards invited me join him for a run on the Gauley a few weeks later. At another race Phil Allender got sick, and I was asked to race with the ARRF team of Joe Monahan and Todd Martin. These guys were serious party animals. They carried a wineskin down the course and passed it around before attempting the team gate. Naturally I had to continue the tradition.

In the Spring of 1973 I drove down to the Savage in a pouring rain. I was forced to stop and spend the night in a rest area because the weather got so bad. The next day, just outside Luke, a boulder big as a house rolled into the road. Dozens of racers were stuck behind it. We waited an hour or so for road crews to arrive. They dynamited the boulder and pushed the debris aside so we could continue. When we got to the Savage it was running at 2500 cfs, two and a half times what we expected. The speed and power was truly impressive. Many people who made the long drive took one look, then left! Those of us who stayed modified the course and spent the entire morning trying to paddle it. Everybody rolled a lot, but after the first round of practices when a dozen boats were lost there were very few swims. Tom Irwin won the National C-1 Championships with the best run of the day, but the rest of us were happy to survive. After Saturday’s runs I took a wild run trip down the entire river with Bill Kirby, skirting huge holes above the Triple Drops and sneaking Memorial Rock on the far, far left. Late Sunday afternoon Ed Gertler and I went creeking after the race.

Years later I met my wife at the Savage. But that’s another story.

Until now U.S. Team members were either full-time students or held jobs. But in the winter of ‘71-‘72, Jamie McEwan and a group of other racers postponed their other commitments to train with Tom Johnson in Kernville, California. They camped in vans along the Kern River at a spot they called “Peanut Butter Park”. They worked out every day in moving water gates, and that spring they dominated the racing circuit. Several of them made the Olympic Team. When Jamie won his bronze medal in Augsburg, Germany he inspired Jon Lugbill, Davey Hearn, and a whole new generation of whitewater competitors.

Here I learned that the selection of the U.S. Team was a political event as much as an athletic one. Jay Evans, the coach of the U.S. Whitewater Team, was a dedicated volunteer who had a lot of influence. For years he picked the team himself! He wanted to concentrate his limited financial and coaching resources (everyone paid most of their own expenses) by selecting a small team that was comprised only of people who he thought could win a medal. Most of them, not surprisingly, came from Dartmouth. Mid-States paddlers believed that only Eric Evans and Jamie McEwan had any chance to win a medal. They felt that we should field as large a team as international regulations allowed to allow our athletes to be seasoned by high-level competition. Even those who did not win medals would be valuable to our racing program as coaches and officials. This philosophical difference caused endless argument.

Jay was also not happy about being responsible for teen-aged competitors. He tried to keep Lynn Ashton, Cindy Goodwin, and Louise Holcombe off the Olympic Team because “those teenaged girls” would distract his male kayakers from their training. But they were great competitors, and he was overruled. But this year Kevin Lewis, now an AW director, qualified for the U.S. team in C-1 at age 15. Jay refused to take him because he “was a coach, not a baby-sitter”. There was also a controversy about Steve Draper and Mikki Piras in C-2 Mixed (C-2M). Steve met Mikki, a Penn State varsity gymnast, and convinced her to paddle doubles with him. After training together for less than six months they made the team, beating several more experienced pairs. There was much unhappiness about allowing such a “green” doubles pair to qualify for the team, but they did well in Europe. I was not a contender, so I hung out with friends as the arguments continued until late at night.

A man is always going to be physically stronger than his female partner, so it takes excellent communication and plenty of practice to keep a canoe under control in slalom gates. Take two competitive individuals, place them in C-2’s, add whitewater, cook under pressure, and fights will erupt. Add a little sexual tension, and things get pretty hot. I was sitting on shore watching practice runs at Loyalsock when the top four C-2M teams started screaming at each other. It really didn’t matter if they were married, travelling as boyfriend and girlfriend, or simply two athletes training together.

I also remember the impressive team of Chuck Lyda and Marietta Gilman from California. Chuck. At 6’ tall and 180 pounds, he was one of the most powerful whitewater athletes of his era. Mary was a petite blonde, weighing less than 100 pounds, who wore butterfly decals on her helmet. In those days, men paddled bow for maximum power and women controlled the boat from the stern. Marietta maintained control of their boat despite their huge physical differences. The other women who paddled C-2M joked that Chuck was simply paddling a big, heavy C-1. But when they got in the boat with him they could not control it! Unfortunately, C-2M is no longer contested internationally. The Eastern Europeans got tired of having their teams defect, and lobbied hard to eliminate it. But before this happened, the Chladeks and the Sedlviks made their escape from Czechoslovakia. Both couples came to the U.S. and contributed a lot to the sport.

A few weeks later Norm Holcombe and I tried out for the U.S. Wildwater Team in C-2. We lived several hours apart, but planned to work out individually on weekdays and paddle together at the races. We never had a chance. This year several excellent doubles teams trained together daily, including two pairs from Philadelphia and the Braman’s, a father/son team from upstate New York who were active in marathon racing. We finished 6th. But Norm had won a spot the slalom team in C-2M the previous week with his wife, Barb.

At the end of each day we trained on a slalom course hung from the Appalachian Trail Bridge. There were just four gates, not the elaborate setup you see today. I got into excellent shape. I decided to make a full-scale try for the 1975 U.S. Whitewater Team. But I needed to make a difficult choice. Although I loved slalom, I knew that my chances of making the team in C-1 were very poor. Behind Jamie McEwan were people like Angus Morrison, Tom Irwin, and several other boaters who usually beat me badly. But the competition was much less intense in C-1 wildwater. I made myself a wildwater C-1 and started working out in earnest.

At the end of each day we trained on a slalom course hung from the Appalachian Trail Bridge. There were just four gates, not the elaborate setup you see today. I got into excellent shape. I decided to make a full-scale try for the 1975 U.S. Whitewater Team. But I needed to make a difficult choice. Although I loved slalom, I knew that my chances of making the team in C-1 were very poor. Behind Jamie McEwan were people like Angus Morrison, Tom Irwin, and several other boaters who usually beat me badly. But the competition was much less intense in C-1 wildwater. I made myself a wildwater C-1 and started working out in earnest.

Mikki Piras, who had also worked at NOC, had moved to DC to train for the wildwater team. Through her I met a coach from the U.S. flatwater team, refined my stroke, and developed a training schedule. Back in Philadelphia, training alone, I paddled intense 3-hour daily workouts on the Schulkill River throughout the winter. I only missed a few days due to extreme cold. I took regular whitewater training runs on weekends with the doubles teams from the Philadelphia Canoe Club, covering ten to twenty miles at a fast clip. But solo training was not without its pitfalls! One frigid night my trusty Norse paddle snapped miles downstream, and I found myself swimming in the icy water. Fortunately I was wearing my shorty wetsuit! I quickly swam to shore, stashed my boat, and staggered out to East River Drive. I soon realized that with my large size and strange clothes no one was going to give me a lift. So I ran four miles back to the Philly Canoe Club where I sat in their shower for a long time.

By Spring I was in the best shape of my life. I won a couple of downriver races and even moved up a few positions in slalom. I knew I couldn’t beat Al Button, the muscular ex-marathon racer from Minneapolis who had designed his own wildwater C-1 (the Seagull) and paddled on both sides with equal skill. I thought that Tom Irwin, who I could never compete with, would probably take the second wildwater team slot. But the third spot would be mine!

By Spring I was in the best shape of my life. I won a couple of downriver races and even moved up a few positions in slalom. I knew I couldn’t beat Al Button, the muscular ex-marathon racer from Minneapolis who had designed his own wildwater C-1 (the Seagull) and paddled on both sides with equal skill. I thought that Tom Irwin, who I could never compete with, would probably take the second wildwater team slot. But the third spot would be mine!

That was not to be. A few weeks before the team trials were held on the Yough my workouts started feeling sluggish. I just didn’t have any snap! At the Yough, I took a long warm-up but still didn’t feel right. I did O.K. in the rapids of the loop, but lost lots of time in the long flat stretch between the bottom of Railroad Rapid and the top of Swimmers. In the end, I lost “my” slot to people I had beaten earlier in the season. Looking back on it, I think that I was probably over-trained and should have cut way back on my workouts before the race. But working alone, without a coach, I just didn’t see it. The guys who beat me simply trained smarter. The next day I went over to the Cheat, hopped in my slalom boat, and played the river with total abandon. At the takeout, I wasn’t the least bit tired.

Although I continued to race for several more years, I never trained with that intensity again. As I passed my 30th birthday the children of my citizen racing buddies were reaching maturity. The Lugbill Brothers, Jon and Ron, made the U.S. Team in ’75 at age 14 and 15. They were a great pair, and this time no one griped about their age. In the years that followed they, along with Dave and Cathy Hearn, lead the “D.C. Kids” to worldwide fame. They dominated the 1979 World Championships in Jonquiere, Quebec, Canada. And that was just the beginning.

Our old practice of leaning back to “duck” your stern under a pole was much easier in this low-volume design. The “kids” evolved the technique further. Kent Ford told me about one night when the group was practicing at the David Taylor Model Basin, a huge indoor pool used for testing naval ship hulls. They stared competing to see who could sneak under a gate the furthest by lowering one pole down into the water. Soon they decided that it was easier to see whose bow could climb up higher on the opposite pole. This quickly evolved into the stern pivot turn, which lifted the bow out of the water for lighting fast spins. Kayakers watched the C-boaters, learned from them, then re-worked their gear and skills. Racers throughout the world copied them. Later, pioneering West Virginia squirt boaters turned this move into the stern squirt. Many other squirt and rodeo moves evolved from here.

Their coach, Bill Endicott, turned training for whitewater events into a science. The U.S. Slalom Team became the one to beat in international competition. With success came financial support. Where once the athletes camped out at the Worlds and lived on peanut butter, now their expenses were met by sponsors. Eventually elite boaters in each class were “sponsored”. It was exciting to watch this develop. But I couldn’t fit into the small slalom boats or, more importantly, compete with all this young talent. By the late 70’s my finish at big races dropped from “the top ten” to the high teens and beyond. It was time to move on.

I was not alone. When I started paddling, the boat designs that the top competitors used were the same ones that everyone wanted for river running. But this changed when the low-volume boats arrived. Race courses kept getting tighter and tighter until you couldn’t possibly make the moves without one. But these small boats were just too small and unstable for most river runners. As the athletes became more talented, fit and focused it was harder for a citizen racer to realistically aspire to racing glory without also planning to quit their job and train full-time. By the early 80’s the first roto-molded kayaks appeared. The River Chaser was followed by the Mirage, then the Dancer. The Dancer was much too short to be race-legal, but by now no one cared. So ironically, as the U.S. produced more world-class racers than anyone, lots of citizen racers like me dropped out. Attendance flagged, and races that used to draw several hundred competitors ended up with a few dozen. So despite the growth of whitewater kayaking, there are probably fewer racers today than there were in the late 70’s. Racers used to be role models for the whitewater community; now that role is filled by competitors in the booming sport of whitewater rodeo.

I stopped traveling to races, and began working as a safety boater for raft trips on the Cheat River.. By this time you could actually walk into a store and buy a kayak, and paddlers could learn the skills they needed without racing, Most of the strong boaters I ran with in the 80’s, like Johnny Brown, Peter Zurfleigh, Jim Hammil, Al Louande, and Pete Skinner; had no racing in their backgrounds. I began cruising up to northern New York to paddle with Skinner and his bunch. I got called occasionally to help with race safety at the Savage, which was always a good excuse to run the river see old friends. Sadly, releases on this river have been curtailed during the last decade by fishing interests. This is a real loss to paddlers everywhere, and I hope we’ll find ways to get back on the river in the future.

I stopped traveling to races, and began working as a safety boater for raft trips on the Cheat River.. By this time you could actually walk into a store and buy a kayak, and paddlers could learn the skills they needed without racing, Most of the strong boaters I ran with in the 80’s, like Johnny Brown, Peter Zurfleigh, Jim Hammil, Al Louande, and Pete Skinner; had no racing in their backgrounds. I began cruising up to northern New York to paddle with Skinner and his bunch. I got called occasionally to help with race safety at the Savage, which was always a good excuse to run the river see old friends. Sadly, releases on this river have been curtailed during the last decade by fishing interests. This is a real loss to paddlers everywhere, and I hope we’ll find ways to get back on the river in the future.

For many of us who raced in the 70’s, it was the fulfillment of a long-time dream. Finally, the Euros who we had learned so much from and looked up to for so long were coming here. They, not our guys, would deal with jet lag, bad food, culture shock, and unfamiliar whitewater. I joined many other ex-racers in a three-year effort to make the event work, coordinating a fifty-person safety team. I saw Jon Lugbill make what was arguably the two finest C-1 runs ever seen at a World Championship to win the gold medal. But more than that, I saw a lot of familiar faces along the shore. The old gang was gathering at the river one more time!

In the winter of 1973 I found a help-wanted ad for river guides and kayak instructors in the American Whitewater Journal. I sent my application to a place called the Nantahala Outdoor Center in North Carolina and in due course was offered a job. Being a Northern boy, I remember being apprehensive as I drove south the next spring. I’d paddled in the Smokies on two previous occasions with Jack Wright, and the locals seemed friendly enough. I’d also met lots of likable Southern paddlers at races. But I’d seen the attacks on civil rights protesters on TV as a kid, and more recently watched the movie Deliverance. My Dad, who watched the movie with me, couldn’t understand why I wanted to go DOWN THERE. At a truck stop in East Tennessee I passed up a baseball cap that said, “Keep the South beautiful, put a Yankee on a bus!” I was worried about fitting in.

I shouldn’t have been concerned. Once I got to the Center, I quickly found myself among friends. But I quickly encountered two distinct types of Southern personalities. One was the strong, calm, thoughtful type exemplified by my boss, Payson Kennedy. In another era he might have been a thoughtful confederate officer. The other was the loud, aggressive, redneck kind personified by my coworker, Donnie Dunton. He was the guy you wanted with you in the trenches!

Payson Kennedy, a former university librarian, had been paddling Southern rivers for decades. A tall man with an athletic build, he was formidable open canoeist. He was also a savvy whitewater guide, an innovative instructor, and a fierce competitor. He’d been a consultant and stunt double in the movie Deliverance. The next year he took the money he’d earned and purchased, with several other investors, a riverside motel (The Tote N’ Tarry) on the Nantahala River. During the next two summers he ran an outfitting business on weekends, going full time when the university closed for the summer. Mostly he employed his family and friends. The previous year Jimmy Holcombe became his first “real” employee.

In 1973 he quit his job and moved to the mountains with his family. The NOC was gearing up for growth, and this meant hiring a staff of about 40 people for the ’74 season. His guides included a handful of top-ranked slalom racers, an assortment of colorful river characters, and the usual college summer work crowd. We all had a lot to learn, and I suspect that some of us would not be hired today.

Donnie Dunton was a short, stocky little dude who stood about 5’4 tall and weighed nearly 260 pounds. He had a bushy brown beard, a huge folding belt knife, and a cowboy hat with a turkey feather in it. He was a friend of Joe Cole, NOC’s river photographer, and when Joe came top the Center he brought Donnie along. Although I never found out exactly where he came from he spoke with the sharp twang of the Southern Appalachians. He was loud, outspoken, quick-tempered, and profane. But because he was competent, unpretentious, and hard-working, the folks at the Center overlooked his rough side and found that behind his bluster was a good-hearted person who you could depend on in tight situations. Our guests either loved him or hated him. Although he was the NOC’s most-requested guide that summer, there were others who asked for “anybody but Donnie”.

I worked regularly with Donnie over on Section IV of the Chattooga. Back then we drove down under the Route 76 Bridge on a dirt road, blew up our rafts with hand-pumps, and waited for the guests. Guides would sit in their boats and wait for the guests to pick the one they wanted to ride with. Conservative customers who wanted a smooth, safe ride chose big, clean-shaven people . . . . like me! Rowdies who wanted big excitement chose guides who looked like Donnie. Unfortunately, the leftover wimps and weenies who wanted someone to mother them down the river chose female guides and the women always got the prize-winning bad crews. For example, I never knew that you could get a four-man raft through the narrow chute at Center Crack until the day that Mikki Piras’ guests stopped paddling and her boat got pushed through . . .on edge! Nowadays nobody allows the guests chose their guides on site anymore!

Occasionally the personalities of crews and guides clashed. One time my trip was approaching Seven-Foot Falls when we noticed that the trip ahead of us had pulled over below the drop. When we got into the eddy, their tripleader asked if I would switch places with Donnie. I did, and finished the run with a nice group from a North Georgia church. They wouldn’t tell me what the problem was, but I later learned from my buddies that Donnie, at the lip of the drop, had screamed at them: “Paddle, you klutzy mother@#%@’s, PADDLE! The group pulled over and refused to continue until they were given another guide.

Guiding Section IV is serious business, so I appreciated Donnie’s frustration. My approach to getting the attention of a spaced-out crew was a bit sneakier. If my guests didn’t pay attention in the first rapid, Screaming Left Turn, I’d let the current take us under a low, overhanging rock. It was a harmless, but somewhat unpleasant experience. I’d duck down quickly and listen to my guests scream as the rock passed overhead. When we got free, I’d pop up and tell them soberly that they’d almost gotten us all killed, and that if they weren’t going to pay attention and work together, I was going to quit right there. It always worked!

Payson taught us how to work closely with each other while running the Five Falls. At Corkscrew, the first guide ran down the shore and set up a throw rope, Then the second boat went through. Soon the safety man was relieved so he could head back upstream to run his raft down. Later arrivals headed across the pool and set up ropes for Crack-in-the-Rock. Not every other company’s format was so smooth and well-controlled. I remember “sitting safety” with Payson when a competitor’s trip floated into Right Crack. The first boat hung up on a big log jammed in the crack and wrapped, then a second boat arrived and piled on top of the first. Guests were screaming and scrambling. One of the guides looked at Payson with a terrified expression and wailed, “Whaddo I do now?” We weren’t too sure, but pitched in and helped untangle the mess. Afterwards Payson smiled at me and said, “Those folks are our best advertisement”.

The next rapid, Jawbone, moves right on into Sock-em-Dog, a big pourover. We needed to get our boats into the left eddy, below “Hydro-Electric Rock”, to set up for “The Dawg”. This could be a dicey maneuver with guests, so we stationed two rope-throwers in the eddy. One day Donnie and I were on duty when Scott, a rather high strung guide, floated by. He was screaming for a rope. Donnie and I threw simultaneously, and our ropes collided overhead. Donnie threw away his entire rope on his second throw; I set up for my second toss, slipped, and landed flat on my back. By this time Scott had run aground on a small rock above “The Puppy Chute”, but he didn’t realize this and the pitch of his screaming went up an octave. Donnie and I started laughing at him, and at ourselves, and this just made matters worse! On another occasion Bob Bouknight, one of Donnie’s rowdy buddies, simply gave up on an unresponsive crew. He bailed out the back of his raft, swam to shore, and his guests went over Sock-em-Dog without him!

The reason for all this consternation was that Sock-em-Dog could be really nasty. I didn’t mind hard-boating it, but I really hated to raft it at higher flows. When you hit the bottom, the pourover often ripped the guide out of his back seat and shoved him way underwater. I usually tried to talk another guide into taking my crew over. Payson kidded me about this until one day he fell out at the base of the drop. He came up bloody! Something (perhaps the remains of an aluminum canoe that Ray Eaton lost there a decade earlier) cut through his life vest, his 1/8″ wetsuit, and into his back! After this experience, the NOC developed a policy of carrying or sneaking the drop at higher flows.

Visiting Clayton, Georgia today, it’s hard to picture it the way it was in ‘74. Today it’s a progressive, tourist oriented place. Chain restaurants and motels line the highway, and the people are very supportive of paddling. But I remember a rough little hill town where some of its residents liked to get drunk and kick hippie paddlers around on Friday night. I remember a town so tough that guides who needed to buy beer went in groups so that they wouldn’t get beaten up at the Piggley-Wiggley! . Even mainstream locals didn’t take kindly river running. The head of the rescue squad, before he was sanctioned by Payson’s lawyer, once remarked to the press that it was too bad that outfitters were taking money from people, running them down the river, and killing them! This was the same man who threw sticks of dynamite into Woodall Shoals to release a trapped body! In fact, although there have been many close calls, no commercially outfitted guest has ever lost their life.

Most of the fatalities were fools trying to re-live the movie Deliverance. Others were non-paddling locals. And there could have been more! Once our safety kayaker rescued a half-drowned woman who had fallen into the river at the top of Woodall Shoals, a long, ledgy Class IV. She reeked of alcohol, and the guide told her that she ought to stay away from the river when she was drunk. A few minutes later her husband arrived, red faced and angry. Waving a tire iron, he wanted to know who had called his wife a drunk! Only a fast retreat into the river prevented bloodshed,

But Donnie knew how to handle these guys, and soon became our unofficial ambassador to the redneck community. We were setting up our Chatooga trips under the Route 76 Bridge when a local guy tried to drive his Jeep CJ straight up a steep embankment under the bridge. After watching this foolishness for a while Payson wandered over and politely suggested to the man that he use the road located just downstream. The man was roaring drunk, and he staggered out of his car screaming and cursing. When our guides hustled over to see what was going on, the man got spooked. Reaching into his pocket, he pulled out a pocketknife and flashed its rusty blade. “You oughtn’t to press a man.” he warned, “A fella could git cut.”

Donnie moved smoothly up to the front of our group. He opened his huge folding knife and offered it gently to the man, handle-first. ” ‘Long as we’re talking about cuttin’, I’d just like you to FEEL this blade.”

Donnie was an expert woodcarver and the blade of his knife was razor sharp. The man slowly ran his finger down the blade. Suddenly, he let out a yelp as the honed edge drew blood. He dropped the knife and it fell to the ground. Donnie retrieved it quickly, then remarked in a friendly way, “Ooo, sharp little @#%@#, isn’t it? You’d better git on home now, before someone gets hurt!”

Some of our guests really liked Donnie’s style, and some got more fun than they bargained for. Donnie spent a long afternoon guiding the Nantahala with to a group of guys who let him know in no uncertain terms that they were not impressed with the river. He put up with this smart talk for most of the run, then above Nantahala Falls he turned to his guests and smiled wickedly. “You boys want THE BIG RIDE?” he asked. They did, and he delivered. He dropped his four-man sideways into the top hole of Nantahala Falls, a steep, nasty hydraulic known for its powerful retentive characteristics. Donnie bailed out the back as his raft began a lengthy surf. One by one the guests were thrown out, recirculated in the hole, trashed in the falls, and spat out. Donnie swam to an eddy and watched from shore, laughing.

Another day his guests got the upper hand! We were doing a high-water run on Section 3 when I noticed that Donnie’s raft was sneaking up on my boat in a flat section. I suspected that he and his crew were planning to board us, so I asked my guests if they wanted to participate. The group, two middle-aged dentists and their wives, declined. I turned around and yelled, “Donnie, you take your crew and go bother someone else!”

Donnie yelled back, “Walbridge, I can’t do nothing about it!” It was then that I realized that the group had taken Donnie’s paddle away! As they closed in I put down my paddle, stood up on in the back of the raft, and told the approaching pirates that there was no way they were coming aboard. But I never had a chance! Three huge men threw me and my two dentists out of our raft. They pitched Donnie overboard, too. They left us with a boat, but no paddles! They made the dentist’s wives lie in the bottom of their raft and poured water on them with bailing buckets. My first thought was that those idiots were going to get themselves washed over Bull Sluice, a stout Class V ledge at that level, so we sent the safety kayaker chasing after them. Then we borrowed spare paddles from other boats on the trip and set off in hot pursuit. We pulled them over just upstream of the big drop, deflated their boat, and sent them hiking down to the takeout.

The NOC didn’t have an outpost the first few times I went over to work the Chattooga. We just drove off into the woods to camp, which made us a tempting target for harassment by local rowdies on motorbikes. But Donnie, always armed and dangerous, pulled out his pistol at the first sign of trouble. The locals spotted the gun and left us alone, so I always camped near Donnie! Later Payson rented us guide quarters: a converted chicken coop behind the Wolverton Mountain Shell (This old gas station on the South Carolina side of Route 76 is now a deli-restaurant). This was a truly marginal facility, with more bugs inside it than out. After getting eaten alive one night by God-knows-what I promised myself that I’d always sleep in my truck. But we never did get much sleep. “Banty roosters”, half-wild male chickens, lived in the trees around the place and would start crowing at around 4:00 AM. We tried to catch them, but the scraggly little buggers could fly and we never got a one. Then one morning a very hung-over Donnie went out and shot a half-dozen of them with his pistol. We soon learned that a neighbor felt that he owned the miserable birds, and Donnie had to make restitution.

NOC grew like crazy that summer, and we were always short of vehicles. The worst one in our fleet was a blue van that we kept parked over behind the restaurant. Garbage was loaded inside and hauled a mile or so up the road to a dumpster several times daily. But when we got real busy we hosed out “the garbage van”, covered the holes in the floor with folded rafts, and loaded our guests on top.

This worked well enough. But at a mid-summer staff meeting, Payson told us that referring to this rattle-trap as “the garbage van” in front of our guests was bad for the Center’s image. He asked that we refer to it in the future as “the GMC Van”. The next day we were swamped. As an overflow crowd watched, I tried to follow Payson’s directive. “Hey, Donnie!” I yelled across the parking lot, “Go get the GMC van.”

“The what?” he yelled back.

“The GMC Van!” I screamed.

“The WHAT?”

“You know, the old blue van parked over there behind the restaurant.”

“Oh, you mean the GARBAGE van. I’ll hose it out right now!”

The Blue Van’s front end kept getting looser and looser, and somebody drove it into Wesser Creek the following summer. It got pulled it out and set on blocks at the far end of the old store. When it caught fire there a few months later, nobody was sorry.

The staff was hard on the vehicles, and my moment of truth came after a particularly grueling stretch of duty. After a late night patching boats in Wesser, I rose at 5:00 AM and drove two hours to the Chattooga. After a long day guiding on Section IV, I returned to the Center at 10:00 PM. I was not pleased to find out that it was MY turn to help clean the restaurant kitchen. When we finished that job a little after midnight Payson asked me to take some things across the river to the Stone House. I fell asleep on the way back, waking up as the van buried itself into the iron superstructure of the Appalachian Trail Bridge! Fortunately, I was going pretty slowly and only cracked a couple of ribs. But I was sore as hell and wasn’t going to be guiding for a few days! Several staff loaned the center personal vehicles to take up the slack.

Every day was an adventure in logistics. One morning we were sitting around with a bunch of restless guests at the Chattooga Outpost waiting for our man Hugh to bring the school bus back from Earl’s Ford. Payson sent Bob Bouknight and me to see what the hold-up was. Now, Earl’s Ford Road was high-crowned stretch of Georgia red clay and it was real slick from recent rains. Hugh had slid off the crown into the formidable gully that served as a ditch. He was stuck and we couldn’t pull him out. Worse, neither of us knew where to find a tow truck big enough to do the job. As we were driving back to the outpost we saw a logging truck parked in front of a small house. Bob had an idea. He knocked on the door and a few minutes later we were driving back to Earl’s Ford in the man’s big rig. He pulled the bus out easily with his winch and only charged us twenty bucks.

We went back to the trucker’s house and sat in our vehicle, waiting for Hugh. When he didn’t show, we drove back down and found that Hugh had slid into the ditch AGAIN! Back we went to the trucker’s house. He was all dressed up and didn’t seem too glad to see us this time. He drove down, pulled the bus free, then dragged it about a half-mile up the road before setting it loose. When Bob gave him another twenty, he just shook his head and smiled. “I’ll be going to church now, then over to my mother’s for dinner. I won’t be back here until after three. You boys think you can keep that bus on the road?”

Later that summer an alarming number of staff drove Center vehicles off Needmore Road, a dirt track over by the Little Tennessee. There had been no serious damage or injuries yet, but Payson was alarmed at the size of the towing bill. So he announced at a staff meeting that we all needed to be a lot more careful. As added motivation he decreed that, rather than letting staff call for a tow truck themselves, any mishaps must be reported directly to him. Afterwards a rather obnoxious fellow named Robert (who had no supervisory responsibilities) got up and remonstrated the group on our careless driving habits. Afterwards several of us remarked that it would be really nice if Robert was the next person to have a problem.

We got our wish! A few days later Robert pulled the Center’s brand-new van over to the side of the road to let a car pass. The shoulder crumbled, and he and the van went into the “Little T”. Robert was unhurt, but the van was sitting on its side in three feet of water. As we drove back to the Center Robert become visibly nervous. “Would you guys come in with me?” he asked.

We wouldn’t have missed it for anything!

As we entered Payson’s office, he regarded us with his usual open, friendly expression. We watched with perverse satisfaction as Robert stuttered and mumbled his way through an account of the mishap. Payson’s expression never changed, but he was quiet for a moment. Then he said softly, “My, that’s aggravatin’!”

Payson’s patience was legendary, and he seldom raised his voice. Once he had to deal with a guy named Gil. Part of Gil’s job was to go around to local motels and restaurants to offer the owners complementary trips down the Nantahala. Payson hoped that these fellow businessmen would then recommend the Center to their guests. Time passed, and Payson became suspicious. At first he thought it was remarkable that so many attractive young women owned area businesses, but then he realized that they didn’t. Gil was handing out passes to various cute receptionists and waitresses that he wanted to get lucky with. One day, after Gil indiscreetly shared the details of his sexual adventures with one too many people, Payson called him into his office and demanded an explanation. Gil responded with a long, winded, profane tirade about the unfairness of his employer. His raised voice carried across Route 19 into the store. Finally, when “Ed” stopped for breath, Payson said to him quietly, “You know, I have always tried to like my employees, but I do believe you’re starting to piss me off.” It would be “Ed’s” last day of work at the Center.

The Nantahala in the summer of ’74 was a fishing stream that was becoming overrun with paddlers. The local anglers were a rough bunch. They all carried pistols (“Fer snakes . . . the two legged kind! Har! Har!”) and they often waved them at paddlers to help make a point. Trees were felled into the river, cars got vandalized, and the Center was regularly threatened with arson. Because an outfitter shop had been torched over on the Locust Fork in Alabama at about the same time this didn’t help anybody sleep at night.

There was some real culture shock at work here. Since people who were on the run from the law settled the area around the Center some folks thought that we were all on the lam, too. And they didn’t appreciate our city ways. Payson and his wife, Aurelia enjoyed church music and often visited local churches. One Sunday they stopped by the church on Wesser Creek and were sitting in the pews as an older man named Larus, who worked the counter at the store, preached. Larus delivered a fire and brimstone denunciation of boaters for, “walking around in their underwear” (wearing bikinis), public drinking, supposed drug and sexual irregularities, and paddling on Sunday. If Payson was shaken, he didn’t show it afterwards. On Monday Larus was back behind the counter, just like always.

Those Nanty fishermen were tough! One day I was working a Nantahala clinic when someone told me there was trouble downstream. Two of our teen-aged guests had found some beers floating in the river, and they were getting ready to open one when an angry, armed local appeared. This was a potentially serious problem. Those were his beers! And Swain County, which the Nanty runs through, is dry. The nearest beer store is an hour away. We did some fast talking, with plenty of yes-sirs and no-sirs, to defuse the situation.

Some of the locals were just plain impossible! There was a old guy over on the Little Tennessee who had a farm down by the river. We met him on a day after the river at floodstage trashed one of our clinics and we needed permission to cross his land. He was helpful then, but he gradually became convinced that canoeists were out to steal his cattle. He started appearing on the shore with a shotgun. He threatened everyone, including Louise Holcombe’s petite, gray-haired mother Beth when she accompanied a class. We tried hard to accommodate him. First he didn’t want us to get out on shore, then he didn’t want us catching eddies on his side of the river because it upset his wife, then the eddies on the other side were off limits, Finally he didn’t want us running the river at all. Payson and I drove over to his house and tried to negotiate a lasting agreement, but the peace only lasted a few days and he was at it again! Later that season, after he took a pot-shot at Dick Eustis, the Center was forced to go to the law and press charges. He ended up doing some prison time.

Donnie really liked to fish, too, and he had no patience for unruly paddlers. I was leading an Outward Bound group down the Nanty one afternoon when I saw a fisherman standing in some mid-stream shallows far ahead. I went down the line of boats, telling everyone to pass behind the fisherman near the right shore. As we got close, I saw that the fisherman was Donnie. I eddied out nearby to chat:

“Hey, Donnie! You catchin’ anything?”

“Walbridge, your group’s the first one that showed me any respect! Them damn canoeists been runnin’ over my line all day!”

“Sorry to hear that.”

By this time my group had gone downstream, and a couple of NOC’s rental canoes were headed towards us. The paddlers were beginners and their boats were out of control.

“Damn!” Said Donnie. “You see that? I’m gonna teach those scumbitches some respect!”

As the first canoe approached, he reached out, grabbed the gunwales, and flipped the unlucky paddlers over. Cursing, he grabbed floating paddles and gear and hurled them downstream after their owners. Then he turned and did the same thing to the second canoe!

“Payson isn’t going to like this!” I mumbled to myself as I paddled downstream. But secretly I thought it was a pretty good lesson. So I didn’t squeal on Donnie when the guys at the store said that some renters had complained about being attacked by a river troll.

The Center rented 16-foot Blue Hole OCA’s which they “blocked” with huge pieces of Styrofoam in the center. This flotation was heavy, but it made our canoes hard to damage. Occasionally one got pinned anyway. When the guests got back to the Center and reported the mishap, whoever was hanging around the store got sent out to recover it.

Donnie and I were driving upriver to release a canoe stuck in Delbar’s Rock Rapid when we saw a Florida tourist on the shoulder throwing rocks at a rattlesnake. Donnie, an avid snake-hunter, got excited.

“Damn,” He said, “That’s a big one! Pull over in there!”

I pulled over and Donnie hopped out, grabbed his Norse guide paddle, and ran up to the man.

“That ain’t no way to kill a snake!” he yelled. Then, without hesitation, he beat the hapless critter senseless with three wicked fast paddle-chops. Grabbing the snake behind the head with one hand, he used the other to pull out his big folding knife and hold it out to me.

“Open it!” he commanded.

I opened his knife, and Donnie quickly decapitated the snake. He laid the carcass out on hood of the speechless tourist’s white Lincoln and started skinning it. “I have wanted a snakeskin headband for nearly five years” he crowed, “and this is the first snake I’ve seen that’s big enough!”

In a moment he had the skin off and wrapped around a small stick. He took his hat off, dropped the skin inside, and put the hat back on. He laid out his bandanna and carefully butchered what remained of the snake. He threw the guts on the ground, gathered the rest up, and approached the tourist.

“Ya want th’ meat?” He asked, “It’s good eatin’!”

The tourist turned green and shook his head. Donnie quickly tied the snake meat up in his bandanna. He took off his hat, dropped the package inside, and replaced his headgear. We’d turned to walk back to the van when Donnie saw the tourist poking at the snake with his foot. He spun around suddenly.

“Don’t yew touch that head!” he yelled “It’ll bite you till sundown for certain!

After we released the canoe we returned to the Center, where Donnie fried the snake on a wood stove inside the store and passed it around. It tasted a lot like chicken!

All good things must come to an end, and as fall approached I did some serious thinking about my future. It had been a great summer. I’d run some great rivers, met some neat people, won the Open Canoe Slalom Nationals, and even learned to clog-dance. But pay for NOC guides in 1974 was 65 bucks a week, plus room and board. Even with the $10 weekly bonus I got as a “ranked” racer I was losing ground. I actually made more money from a small mail-order business I ran from my room, selling sprayskirt and life vest kits. I’d also been training hard, and wanted to make a serious try for the U.S. Whitewater Team. But weekend racing and guiding just don’t mix!

So in early October I said my good-byes and headed north, first for the Gauley, and then home. Payson, of course, built the NOC into a huge, thriving operation that many people tried to imitate. They’re now the biggest single employer in Swain County. Donnie was diagnosed with cancer early that winter and died a year later. Although he spent many of his last days hanging out at the Center I worked up in Canada the following summer and never saw him again. If there are fish and snakes in heaven he’s probably out there catching some right now. And he’s probably got a side job keeping the rednecks in line at St. Peter’s Gate!

In the 1970’s, long before anyone was a sponsored paddler, the only way to make money by paddling was to be a river guide. Unlike the west, where commercial and private paddlers formed very separate groups, back east, we were all part of the same community. Since there were very few skilled whitewater paddlers around, we often tagged along on commercial trips running the Lower Yough. You got a free lunch and a shuttle in exchange for working informally as an extra safety boat. It was easy to move from this to occasional employment. There were no real “standards” for guides; you just had to be known to the company manager. On busy days “known” paddlers were sometimes approached and offered work as they unloaded boats. My first day of guiding came after my car was broken into and my wallet stolen. When I tried to borrow twenty bucks from Greg Green he recommended me to his boss at White Water Adventurers instead. By the mid-70’s I also tagged along occasionally on Cheat River trips. Business here was growing fast. My friend John Brown, who guided for Mountain Streams and Trails, told me one spring that they were looking for safety boaters on the Cheat. He suggested that I come down for a training weekend and meet “the boys”. Afterwards, I signed up to work several weekends during April and May. Later that Spring I met the company owner, Ralph William McCarty.

Ralph McCarty was a man who spent his entire life “thinking outside the box.” Some people referred to him as “Crazy Ralph” because he had a unique, stream-of-consciousness way of talking. I thought he was crazy like a fox! A lot of his ideas never went anywhere, but some of them were right on target so I always listened carefully. He’d been a successful engineer in the aircraft and automotive industries of the Midwest since the early days of World War II and held several patents. He soon became better known as a riverman. He became an active whitewater canoeist, a founding member of the Mad Hatter’s Canoe Club of Cleveland, and an early instructor at the Western Pennsylvania Whitewater School. In the mid-60’s he went to Ralph Freeze at Chicagoland Canoe and bought a high-performance European inflatable kayak for his son, Mike. Since it was not a self-bailing ducky, he added a full fiberglass deck that would accept a spray skirt to keep the water out. This hot little boats was way ahead of its time

As McCarty reached mid-life he entered the outfitting business. He bought a bunch of those high performance ducks and got Chuck Tummonds, a paddler and fiberglass fabricator, to produce the add-on decks. Mountain Streams and Trails opened in 1967, offering guided ducky trips down the rivers of Western Pennsylvania and Northern West Virginia. Although his main business was on the Lower Yough, he also offered trips down the Casselman, Cheat, Upper Yough, and Lower Big Sandy! In 1968 he bought a single huge raft he called the “Black Mariah” to accommodate friends of ducky paddlers who didn’t want to paddle alone. The spaces on his raft always booked really fast, and he geared up to meet this demand. For this, he designed a unique raft were later referred to as “Ralph’s Rockets”. The side tubes extended back past a square stern to make the boat track better. A guide who knew how could use these stern tubes could climb back aboard very fast after a flip. He then contracted with Rubber Crafters of West Virginia to build them.

In the Spring of 1968 his company, Mountain Streams and Trails (MS&T) ran its first commercial Cheat Trip. His son Mike, who ran the company until 2003, was in junior high school back then. At the Albright Ball Field (now the Cheat Canyon Campground) they used a machete to cut through the thick rhododendron that lined the riverbank to reach the water. (This rhodo and the giant riverside sycamores washed away in the ’85 flood) His plan was to use the Cheat to build his spring business, when the Yough ran at levels that were considered too high for commercial trips. But the Cheat business grew explosively. By the time I arrived in the mid-70’s Cheat Season was bigger than Gauley Season! They were running eight or more trips a day of 50 people each on weekends from Easter to Memorial Day. There was also substantial weekday business. Appalachian Wildwaters was just getting started, and Whitewater Adventurers was running a few trips, but “the boys” from MS&T had the bulk of the business. Soon outfitters from the New River, who were looking for an alternative to high-water spring trips there, came up to run the Cheat.

Guide training was informal but thorough. Potential safety boaters were evaluated by managers and senior guides as they paddled the river. A strong roll was essential and anyone who swam was likely to find himself “pushing rubber.” We also had to learn the river. It’s one thing to run the Cheat Canyon for fun, another to always know exactly where you are so you don’t direct guests someplace where they don’t belong. Experienced safety boaters were paired with rookies who showed them the “guide rocks” and “guide eddies” where we would stop to direct rafting guests away from danger and provide safety back-up. For instance, a sharp piece of metal next to the abandoned railroad bridge below the Albright Ball Field could slash a raft badly. We eddied out next to it and motioned the rafts away. If anything bad happened, we were supposed to converge on the scene to assist. The guides were expected to be excellent river swimmers, and we practiced this skill in the icy March water.

Cheat trips were run using the same “unguided format” used on the Lower Yough. The tripleader gave his safety talk as we drifted downstream from the Route 26 Bridge in Albright. He covered the difference between “small, friendly” and “big unfriendly” rocks and what to do if you fell out of your boat. He also gave the guests a “talk-up” above major rapids while safety boaters assumed their positions. He then lead his trip through the rapid. The “grunt guide” brought up the rear. He carried the group’s lunches and the first aid kit, and was the person responsible for releasing pinned boats. The safety boaters circulated around unless they had a specific assignment, assisting the grunt guide as needed. We always tried to coach the guests to unpin their boats themselves to avoid the hassle of getting out of our boats.

The Cheat Canyon before the ’85 flood was a lot like the Lower Yough, only slightly harder and twice as long. The rapids, except for Coliseum, were pretty straightforward. At the bottom of Decision Rapid people were warned by the tripleader that if they didn’t like what they saw, they should walk out. Some did, especially on those really cold spring days. Beech Run had a big hole halfway down at high levels. Big Nasty was just a big, frisky wave train with no hole. At Even Nastier there’s a pourover rock just upstream of a bad pinning rock. A raft could drop into this slot like toast in a toaster, and you might as well tie it off and wait for the water to go down! A guide always stood on this rock to warn people off and push them off with their feet if they didn’t listen. We ate lunch just below here.

Lunch was a pretty basic affair. Guests had their choice of mystery meat or PB&J sandwiches. There were apples and MS&T’s famous generic soda. Guides told me that the guests were always hungry, and good food would be wasted on them. We’d described the rest room facilities (boys upstream, girls downstream) and told them to throw their apple cores into the woods where a 90 pound chipmunk would clean up. They were cautioned against throwing lunch meat into the woods because that would make the chipmunk carnivorous, and then everyone would have to take their paddles into the woods for protection. Lastly, everyone was told “to put the top of the pop top in the hole in the pop top can” before turning in the can to be carried out. This was a good time to socialize with the guests, but we weren’t above pulling their leg. I remember one day someone asked if any of us were “licensed river pilots”. I told them my buddy Jim had been a barge pilot on the Allegheny River, but that one day his barge got away from him and rammed the Interstate 79 Bridge near Pittsburgh. “And the unemployment office sent him here.” I concluded.

After a long class III stretch known as “the Doldrums” the river starts to pick up fast. After “Cue Ball” “Green’s Hole” and “Teardrop” we arrived at High Falls, a long sloping ledge with big holes that’s exciting at any level. Years earlier John Sweet showed me a great line down the middle that always worked, but it took some courage to get out there in the center at high levels. After Maze Rapid, Coliseum approached. This rapid was quite long and really tough to guide. After going through the “Upper and Lower Box”, a series of tight chutes, the rafters had to skirt “The Devil’s Trap” and “Coliseum Rock”. Below here was “Lower Coliseum”. This is now called “Pete Morgan” to honor a man in Albright who ran a gas station at the Route 26 Bridge. Before the days of the internet and dial-up gauge reports paddlers phoned him for water level readings. At high levels Upper and Lower Coliseum ran together. We always seemed to be about one guide short here, and people sometimes took long swims. But the guests were pretty tough in the 70’s. Most were young men in their 20’s who were hikers, bikers, skiers, or some other type of outdoor athlete. They were looking for a bit of rugged adventure, and they got it. I don’t remember any really close calls.

Rafting back then was not for the faint-hearted. People camped out at Cheat Canyon Campground, which on popular weekends was extremely crowded. Campers sometimes got pretty rowdy, forcing the campground owner, Grant Tichnell, to strap on his pistol and get things back under control. But we were an honest bunch. It wasn’t unusual to come in late at night and find Grant asleep in his chair. We’d tuck five bucks into his shirt pocket (sometimes there was quite a lot of money in there!) and enter the campground without waking him up.

The Albright Fire Department offered breakfast to everyone, and as a result of their partnership with MS&T they had one of the best equipped small-town fire departments in the country. There was no change area at the put-in, just a parking lot and a few portable toilets. But being a progressive company, we allowed the few female customers to change in a parked van or a school bus. Customer service was pretty no-nonsense, and no whining was allowed. Once, while visiting “The Last Resort”, MS&T’s base on the Lower Yough, I overheard someone tell a guest on the phone: “Now sir, I appreciate your position, but please, just remember one thing: I have your money, and you have my sympathy!”