Working for NOC in ’74 – A Yankee Paddler Goes South

In the winter of 1973 I found a help-wanted ad for river guides and kayak instructors in the American Whitewater Journal. I sent my application to a place called the Nantahala Outdoor Center in North Carolina and in due course was offered a job. Being a Northern boy, I remember being apprehensive as I drove south the next spring. I’d paddled in the Smokies on two previous occasions with Jack Wright, and the locals seemed friendly enough. I’d also met lots of likable Southern paddlers at races. But I’d seen the attacks on civil rights protesters on TV as a kid, and more recently watched the movie Deliverance. My Dad, who watched the movie with me, couldn’t understand why I wanted to go DOWN THERE. At a truck stop in East Tennessee I passed up a baseball cap that said, “Keep the South beautiful, put a Yankee on a bus!” I was worried about fitting in.

I shouldn’t have been concerned. Once I got to the Center, I quickly found myself among friends. But I quickly encountered two distinct types of Southern personalities. One was the strong, calm, thoughtful type exemplified by my boss, Payson Kennedy. In another era he might have been a thoughtful confederate officer. The other was the loud, aggressive, redneck kind personified by my coworker, Donnie Dunton. He was the guy you wanted with you in the trenches!

Payson Kennedy, a former university librarian, had been paddling Southern rivers for decades. A tall man with an athletic build, he was formidable open canoeist. He was also a savvy whitewater guide, an innovative instructor, and a fierce competitor. He’d been a consultant and stunt double in the movie Deliverance. The next year he took the money he’d earned and purchased, with several other investors, a riverside motel (The Tote N’ Tarry) on the Nantahala River. During the next two summers he ran an outfitting business on weekends, going full time when the university closed for the summer. Mostly he employed his family and friends. The previous year Jimmy Holcombe became his first “real” employee.

In 1973 he quit his job and moved to the mountains with his family. The NOC was gearing up for growth, and this meant hiring a staff of about 40 people for the ’74 season. His guides included a handful of top-ranked slalom racers, an assortment of colorful river characters, and the usual college summer work crowd. We all had a lot to learn, and I suspect that some of us would not be hired today.

Donnie Dunton was a short, stocky little dude who stood about 5’4 tall and weighed nearly 260 pounds. He had a bushy brown beard, a huge folding belt knife, and a cowboy hat with a turkey feather in it. He was a friend of Joe Cole, NOC’s river photographer, and when Joe came top the Center he brought Donnie along. Although I never found out exactly where he came from he spoke with the sharp twang of the Southern Appalachians. He was loud, outspoken, quick-tempered, and profane. But because he was competent, unpretentious, and hard-working, the folks at the Center overlooked his rough side and found that behind his bluster was a good-hearted person who you could depend on in tight situations. Our guests either loved him or hated him. Although he was the NOC’s most-requested guide that summer, there were others who asked for “anybody but Donnie”.

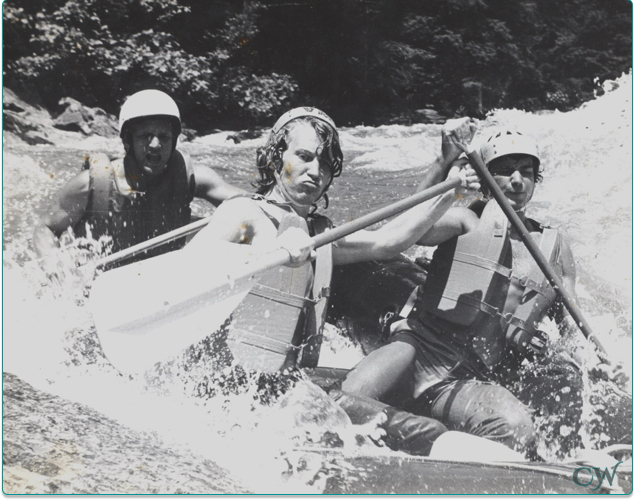

I worked regularly with Donnie over on Section IV of the Chattooga. Back then we drove down under the Route 76 Bridge on a dirt road, blew up our rafts with hand-pumps, and waited for the guests. Guides would sit in their boats and wait for the guests to pick the one they wanted to ride with. Conservative customers who wanted a smooth, safe ride chose big, clean-shaven people . . . . like me! Rowdies who wanted big excitement chose guides who looked like Donnie. Unfortunately, the leftover wimps and weenies who wanted someone to mother them down the river chose female guides and the women always got the prize-winning bad crews. For example, I never knew that you could get a four-man raft through the narrow chute at Center Crack until the day that Mikki Piras’ guests stopped paddling and her boat got pushed through . . .on edge! Nowadays nobody allows the guests chose their guides on site anymore!

Occasionally the personalities of crews and guides clashed. One time my trip was approaching Seven-Foot Falls when we noticed that the trip ahead of us had pulled over below the drop. When we got into the eddy, their tripleader asked if I would switch places with Donnie. I did, and finished the run with a nice group from a North Georgia church. They wouldn’t tell me what the problem was, but I later learned from my buddies that Donnie, at the lip of the drop, had screamed at them: “Paddle, you klutzy mother@#%@’s, PADDLE! The group pulled over and refused to continue until they were given another guide.

Guiding Section IV is serious business, so I appreciated Donnie’s frustration. My approach to getting the attention of a spaced-out crew was a bit sneakier. If my guests didn’t pay attention in the first rapid, Screaming Left Turn, I’d let the current take us under a low, overhanging rock. It was a harmless, but somewhat unpleasant experience. I’d duck down quickly and listen to my guests scream as the rock passed overhead. When we got free, I’d pop up and tell them soberly that they’d almost gotten us all killed, and that if they weren’t going to pay attention and work together, I was going to quit right there. It always worked!

Payson taught us how to work closely with each other while running the Five Falls. At Corkscrew, the first guide ran down the shore and set up a throw rope, Then the second boat went through. Soon the safety man was relieved so he could head back upstream to run his raft down. Later arrivals headed across the pool and set up ropes for Crack-in-the-Rock. Not every other company’s format was so smooth and well-controlled. I remember “sitting safety” with Payson when a competitor’s trip floated into Right Crack. The first boat hung up on a big log jammed in the crack and wrapped, then a second boat arrived and piled on top of the first. Guests were screaming and scrambling. One of the guides looked at Payson with a terrified expression and wailed, “Whaddo I do now?” We weren’t too sure, but pitched in and helped untangle the mess. Afterwards Payson smiled at me and said, “Those folks are our best advertisement”.

The next rapid, Jawbone, moves right on into Sock-em-Dog, a big pourover. We needed to get our boats into the left eddy, below “Hydro-Electric Rock”, to set up for “The Dawg”. This could be a dicey maneuver with guests, so we stationed two rope-throwers in the eddy. One day Donnie and I were on duty when Scott, a rather high strung guide, floated by. He was screaming for a rope. Donnie and I threw simultaneously, and our ropes collided overhead. Donnie threw away his entire rope on his second throw; I set up for my second toss, slipped, and landed flat on my back. By this time Scott had run aground on a small rock above “The Puppy Chute”, but he didn’t realize this and the pitch of his screaming went up an octave. Donnie and I started laughing at him, and at ourselves, and this just made matters worse! On another occasion Bob Bouknight, one of Donnie’s rowdy buddies, simply gave up on an unresponsive crew. He bailed out the back of his raft, swam to shore, and his guests went over Sock-em-Dog without him!

The reason for all this consternation was that Sock-em-Dog could be really nasty. I didn’t mind hard-boating it, but I really hated to raft it at higher flows. When you hit the bottom, the pourover often ripped the guide out of his back seat and shoved him way underwater. I usually tried to talk another guide into taking my crew over. Payson kidded me about this until one day he fell out at the base of the drop. He came up bloody! Something (perhaps the remains of an aluminum canoe that Ray Eaton lost there a decade earlier) cut through his life vest, his 1/8″ wetsuit, and into his back! After this experience, the NOC developed a policy of carrying or sneaking the drop at higher flows.

Visiting Clayton, Georgia today, it’s hard to picture it the way it was in ‘74. Today it’s a progressive, tourist oriented place. Chain restaurants and motels line the highway, and the people are very supportive of paddling. But I remember a rough little hill town where some of its residents liked to get drunk and kick hippie paddlers around on Friday night. I remember a town so tough that guides who needed to buy beer went in groups so that they wouldn’t get beaten up at the Piggley-Wiggley! . Even mainstream locals didn’t take kindly river running. The head of the rescue squad, before he was sanctioned by Payson’s lawyer, once remarked to the press that it was too bad that outfitters were taking money from people, running them down the river, and killing them! This was the same man who threw sticks of dynamite into Woodall Shoals to release a trapped body! In fact, although there have been many close calls, no commercially outfitted guest has ever lost their life.

Most of the fatalities were fools trying to re-live the movie Deliverance. Others were non-paddling locals. And there could have been more! Once our safety kayaker rescued a half-drowned woman who had fallen into the river at the top of Woodall Shoals, a long, ledgy Class IV. She reeked of alcohol, and the guide told her that she ought to stay away from the river when she was drunk. A few minutes later her husband arrived, red faced and angry. Waving a tire iron, he wanted to know who had called his wife a drunk! Only a fast retreat into the river prevented bloodshed,

But Donnie knew how to handle these guys, and soon became our unofficial ambassador to the redneck community. We were setting up our Chatooga trips under the Route 76 Bridge when a local guy tried to drive his Jeep CJ straight up a steep embankment under the bridge. After watching this foolishness for a while Payson wandered over and politely suggested to the man that he use the road located just downstream. The man was roaring drunk, and he staggered out of his car screaming and cursing. When our guides hustled over to see what was going on, the man got spooked. Reaching into his pocket, he pulled out a pocketknife and flashed its rusty blade. “You oughtn’t to press a man.” he warned, “A fella could git cut.”

Donnie moved smoothly up to the front of our group. He opened his huge folding knife and offered it gently to the man, handle-first. ” ‘Long as we’re talking about cuttin’, I’d just like you to FEEL this blade.”

Donnie was an expert woodcarver and the blade of his knife was razor sharp. The man slowly ran his finger down the blade. Suddenly, he let out a yelp as the honed edge drew blood. He dropped the knife and it fell to the ground. Donnie retrieved it quickly, then remarked in a friendly way, “Ooo, sharp little @#%@#, isn’t it? You’d better git on home now, before someone gets hurt!”

Some of our guests really liked Donnie’s style, and some got more fun than they bargained for. Donnie spent a long afternoon guiding the Nantahala with to a group of guys who let him know in no uncertain terms that they were not impressed with the river. He put up with this smart talk for most of the run, then above Nantahala Falls he turned to his guests and smiled wickedly. “You boys want THE BIG RIDE?” he asked. They did, and he delivered. He dropped his four-man sideways into the top hole of Nantahala Falls, a steep, nasty hydraulic known for its powerful retentive characteristics. Donnie bailed out the back as his raft began a lengthy surf. One by one the guests were thrown out, recirculated in the hole, trashed in the falls, and spat out. Donnie swam to an eddy and watched from shore, laughing.

Another day his guests got the upper hand! We were doing a high-water run on Section 3 when I noticed that Donnie’s raft was sneaking up on my boat in a flat section. I suspected that he and his crew were planning to board us, so I asked my guests if they wanted to participate. The group, two middle-aged dentists and their wives, declined. I turned around and yelled, “Donnie, you take your crew and go bother someone else!”

Donnie yelled back, “Walbridge, I can’t do nothing about it!” It was then that I realized that the group had taken Donnie’s paddle away! As they closed in I put down my paddle, stood up on in the back of the raft, and told the approaching pirates that there was no way they were coming aboard. But I never had a chance! Three huge men threw me and my two dentists out of our raft. They pitched Donnie overboard, too. They left us with a boat, but no paddles! They made the dentist’s wives lie in the bottom of their raft and poured water on them with bailing buckets. My first thought was that those idiots were going to get themselves washed over Bull Sluice, a stout Class V ledge at that level, so we sent the safety kayaker chasing after them. Then we borrowed spare paddles from other boats on the trip and set off in hot pursuit. We pulled them over just upstream of the big drop, deflated their boat, and sent them hiking down to the takeout.

The NOC didn’t have an outpost the first few times I went over to work the Chattooga. We just drove off into the woods to camp, which made us a tempting target for harassment by local rowdies on motorbikes. But Donnie, always armed and dangerous, pulled out his pistol at the first sign of trouble. The locals spotted the gun and left us alone, so I always camped near Donnie! Later Payson rented us guide quarters: a converted chicken coop behind the Wolverton Mountain Shell (This old gas station on the South Carolina side of Route 76 is now a deli-restaurant). This was a truly marginal facility, with more bugs inside it than out. After getting eaten alive one night by God-knows-what I promised myself that I’d always sleep in my truck. But we never did get much sleep. “Banty roosters”, half-wild male chickens, lived in the trees around the place and would start crowing at around 4:00 AM. We tried to catch them, but the scraggly little buggers could fly and we never got a one. Then one morning a very hung-over Donnie went out and shot a half-dozen of them with his pistol. We soon learned that a neighbor felt that he owned the miserable birds, and Donnie had to make restitution.

NOC grew like crazy that summer, and we were always short of vehicles. The worst one in our fleet was a blue van that we kept parked over behind the restaurant. Garbage was loaded inside and hauled a mile or so up the road to a dumpster several times daily. But when we got real busy we hosed out “the garbage van”, covered the holes in the floor with folded rafts, and loaded our guests on top.

This worked well enough. But at a mid-summer staff meeting, Payson told us that referring to this rattle-trap as “the garbage van” in front of our guests was bad for the Center’s image. He asked that we refer to it in the future as “the GMC Van”. The next day we were swamped. As an overflow crowd watched, I tried to follow Payson’s directive. “Hey, Donnie!” I yelled across the parking lot, “Go get the GMC van.”

“The what?” he yelled back.

“The GMC Van!” I screamed.

“The WHAT?”

“You know, the old blue van parked over there behind the restaurant.”

“Oh, you mean the GARBAGE van. I’ll hose it out right now!”

The Blue Van’s front end kept getting looser and looser, and somebody drove it into Wesser Creek the following summer. It got pulled it out and set on blocks at the far end of the old store. When it caught fire there a few months later, nobody was sorry.

The staff was hard on the vehicles, and my moment of truth came after a particularly grueling stretch of duty. After a late night patching boats in Wesser, I rose at 5:00 AM and drove two hours to the Chattooga. After a long day guiding on Section IV, I returned to the Center at 10:00 PM. I was not pleased to find out that it was MY turn to help clean the restaurant kitchen. When we finished that job a little after midnight Payson asked me to take some things across the river to the Stone House. I fell asleep on the way back, waking up as the van buried itself into the iron superstructure of the Appalachian Trail Bridge! Fortunately, I was going pretty slowly and only cracked a couple of ribs. But I was sore as hell and wasn’t going to be guiding for a few days! Several staff loaned the center personal vehicles to take up the slack.

Every day was an adventure in logistics. One morning we were sitting around with a bunch of restless guests at the Chattooga Outpost waiting for our man Hugh to bring the school bus back from Earl’s Ford. Payson sent Bob Bouknight and me to see what the hold-up was. Now, Earl’s Ford Road was high-crowned stretch of Georgia red clay and it was real slick from recent rains. Hugh had slid off the crown into the formidable gully that served as a ditch. He was stuck and we couldn’t pull him out. Worse, neither of us knew where to find a tow truck big enough to do the job. As we were driving back to the outpost we saw a logging truck parked in front of a small house. Bob had an idea. He knocked on the door and a few minutes later we were driving back to Earl’s Ford in the man’s big rig. He pulled the bus out easily with his winch and only charged us twenty bucks.

We went back to the trucker’s house and sat in our vehicle, waiting for Hugh. When he didn’t show, we drove back down and found that Hugh had slid into the ditch AGAIN! Back we went to the trucker’s house. He was all dressed up and didn’t seem too glad to see us this time. He drove down, pulled the bus free, then dragged it about a half-mile up the road before setting it loose. When Bob gave him another twenty, he just shook his head and smiled. “I’ll be going to church now, then over to my mother’s for dinner. I won’t be back here until after three. You boys think you can keep that bus on the road?”

Later that summer an alarming number of staff drove Center vehicles off Needmore Road, a dirt track over by the Little Tennessee. There had been no serious damage or injuries yet, but Payson was alarmed at the size of the towing bill. So he announced at a staff meeting that we all needed to be a lot more careful. As added motivation he decreed that, rather than letting staff call for a tow truck themselves, any mishaps must be reported directly to him. Afterwards a rather obnoxious fellow named Robert (who had no supervisory responsibilities) got up and remonstrated the group on our careless driving habits. Afterwards several of us remarked that it would be really nice if Robert was the next person to have a problem.

We got our wish! A few days later Robert pulled the Center’s brand-new van over to the side of the road to let a car pass. The shoulder crumbled, and he and the van went into the “Little T”. Robert was unhurt, but the van was sitting on its side in three feet of water. As we drove back to the Center Robert become visibly nervous. “Would you guys come in with me?” he asked.

We wouldn’t have missed it for anything!

As we entered Payson’s office, he regarded us with his usual open, friendly expression. We watched with perverse satisfaction as Robert stuttered and mumbled his way through an account of the mishap. Payson’s expression never changed, but he was quiet for a moment. Then he said softly, “My, that’s aggravatin’!”

Payson’s patience was legendary, and he seldom raised his voice. Once he had to deal with a guy named Gil. Part of Gil’s job was to go around to local motels and restaurants to offer the owners complementary trips down the Nantahala. Payson hoped that these fellow businessmen would then recommend the Center to their guests. Time passed, and Payson became suspicious. At first he thought it was remarkable that so many attractive young women owned area businesses, but then he realized that they didn’t. Gil was handing out passes to various cute receptionists and waitresses that he wanted to get lucky with. One day, after Gil indiscreetly shared the details of his sexual adventures with one too many people, Payson called him into his office and demanded an explanation. Gil responded with a long, winded, profane tirade about the unfairness of his employer. His raised voice carried across Route 19 into the store. Finally, when “Ed” stopped for breath, Payson said to him quietly, “You know, I have always tried to like my employees, but I do believe you’re starting to piss me off.” It would be “Ed’s” last day of work at the Center.

The Nantahala in the summer of ’74 was a fishing stream that was becoming overrun with paddlers. The local anglers were a rough bunch. They all carried pistols (“Fer snakes . . . the two legged kind! Har! Har!”) and they often waved them at paddlers to help make a point. Trees were felled into the river, cars got vandalized, and the Center was regularly threatened with arson. Because an outfitter shop had been torched over on the Locust Fork in Alabama at about the same time this didn’t help anybody sleep at night.

There was some real culture shock at work here. Since people who were on the run from the law settled the area around the Center some folks thought that we were all on the lam, too. And they didn’t appreciate our city ways. Payson and his wife, Aurelia enjoyed church music and often visited local churches. One Sunday they stopped by the church on Wesser Creek and were sitting in the pews as an older man named Larus, who worked the counter at the store, preached. Larus delivered a fire and brimstone denunciation of boaters for, “walking around in their underwear” (wearing bikinis), public drinking, supposed drug and sexual irregularities, and paddling on Sunday. If Payson was shaken, he didn’t show it afterwards. On Monday Larus was back behind the counter, just like always.

Those Nanty fishermen were tough! One day I was working a Nantahala clinic when someone told me there was trouble downstream. Two of our teen-aged guests had found some beers floating in the river, and they were getting ready to open one when an angry, armed local appeared. This was a potentially serious problem. Those were his beers! And Swain County, which the Nanty runs through, is dry. The nearest beer store is an hour away. We did some fast talking, with plenty of yes-sirs and no-sirs, to defuse the situation.

Some of the locals were just plain impossible! There was a old guy over on the Little Tennessee who had a farm down by the river. We met him on a day after the river at floodstage trashed one of our clinics and we needed permission to cross his land. He was helpful then, but he gradually became convinced that canoeists were out to steal his cattle. He started appearing on the shore with a shotgun. He threatened everyone, including Louise Holcombe’s petite, gray-haired mother Beth when she accompanied a class. We tried hard to accommodate him. First he didn’t want us to get out on shore, then he didn’t want us catching eddies on his side of the river because it upset his wife, then the eddies on the other side were off limits, Finally he didn’t want us running the river at all. Payson and I drove over to his house and tried to negotiate a lasting agreement, but the peace only lasted a few days and he was at it again! Later that season, after he took a pot-shot at Dick Eustis, the Center was forced to go to the law and press charges. He ended up doing some prison time.

Donnie really liked to fish, too, and he had no patience for unruly paddlers. I was leading an Outward Bound group down the Nanty one afternoon when I saw a fisherman standing in some mid-stream shallows far ahead. I went down the line of boats, telling everyone to pass behind the fisherman near the right shore. As we got close, I saw that the fisherman was Donnie. I eddied out nearby to chat:

“Hey, Donnie! You catchin’ anything?”

“Walbridge, your group’s the first one that showed me any respect! Them damn canoeists been runnin’ over my line all day!”

“Sorry to hear that.”

By this time my group had gone downstream, and a couple of NOC’s rental canoes were headed towards us. The paddlers were beginners and their boats were out of control.

“Damn!” Said Donnie. “You see that? I’m gonna teach those scumbitches some respect!”

As the first canoe approached, he reached out, grabbed the gunwales, and flipped the unlucky paddlers over. Cursing, he grabbed floating paddles and gear and hurled them downstream after their owners. Then he turned and did the same thing to the second canoe!

“Payson isn’t going to like this!” I mumbled to myself as I paddled downstream. But secretly I thought it was a pretty good lesson. So I didn’t squeal on Donnie when the guys at the store said that some renters had complained about being attacked by a river troll.

The Center rented 16-foot Blue Hole OCA’s which they “blocked” with huge pieces of Styrofoam in the center. This flotation was heavy, but it made our canoes hard to damage. Occasionally one got pinned anyway. When the guests got back to the Center and reported the mishap, whoever was hanging around the store got sent out to recover it.

Donnie and I were driving upriver to release a canoe stuck in Delbar’s Rock Rapid when we saw a Florida tourist on the shoulder throwing rocks at a rattlesnake. Donnie, an avid snake-hunter, got excited.

“Damn,” He said, “That’s a big one! Pull over in there!”

I pulled over and Donnie hopped out, grabbed his Norse guide paddle, and ran up to the man.

“That ain’t no way to kill a snake!” he yelled. Then, without hesitation, he beat the hapless critter senseless with three wicked fast paddle-chops. Grabbing the snake behind the head with one hand, he used the other to pull out his big folding knife and hold it out to me.

“Open it!” he commanded.

I opened his knife, and Donnie quickly decapitated the snake. He laid the carcass out on hood of the speechless tourist’s white Lincoln and started skinning it. “I have wanted a snakeskin headband for nearly five years” he crowed, “and this is the first snake I’ve seen that’s big enough!”

In a moment he had the skin off and wrapped around a small stick. He took his hat off, dropped the skin inside, and put the hat back on. He laid out his bandanna and carefully butchered what remained of the snake. He threw the guts on the ground, gathered the rest up, and approached the tourist.

“Ya want th’ meat?” He asked, “It’s good eatin’!”

The tourist turned green and shook his head. Donnie quickly tied the snake meat up in his bandanna. He took off his hat, dropped the package inside, and replaced his headgear. We’d turned to walk back to the van when Donnie saw the tourist poking at the snake with his foot. He spun around suddenly.

“Don’t yew touch that head!” he yelled “It’ll bite you till sundown for certain!

After we released the canoe we returned to the Center, where Donnie fried the snake on a wood stove inside the store and passed it around. It tasted a lot like chicken!

All good things must come to an end, and as fall approached I did some serious thinking about my future. It had been a great summer. I’d run some great rivers, met some neat people, won the Open Canoe Slalom Nationals, and even learned to clog-dance. But pay for NOC guides in 1974 was 65 bucks a week, plus room and board. Even with the $10 weekly bonus I got as a “ranked” racer I was losing ground. I actually made more money from a small mail-order business I ran from my room, selling sprayskirt and life vest kits. I’d also been training hard, and wanted to make a serious try for the U.S. Whitewater Team. But weekend racing and guiding just don’t mix!

So in early October I said my good-byes and headed north, first for the Gauley, and then home. Payson, of course, built the NOC into a huge, thriving operation that many people tried to imitate. They’re now the biggest single employer in Swain County. Donnie was diagnosed with cancer early that winter and died a year later. Although he spent many of his last days hanging out at the Center I worked up in Canada the following summer and never saw him again. If there are fish and snakes in heaven he’s probably out there catching some right now. And he’s probably got a side job keeping the rednecks in line at St. Peter’s Gate!